Increasing Retirement Savings through Access Points and Persuasive Messages

Context

Private savings are an increasingly important complement to public pension funds. However, low private savings rates are a concern to policymakers in various regions. In Mexico, income replacement rates at retirement average 40 percent, which might have significant social, micro-, and macroeconomic implications. Many studies have tackled transaction costs and psychological barriers that might prevent individuals from saving. Little research, however, is known to jointly address transaction costs AND psychological barriers.

Mexico introduced a privatized pension system in 1997, which consisted of a defined contribution plan. Additionally, savers could keep voluntary savings separate. Low private savings rates led the Mexican government to implement a series of interventions to increase them.

The Project

The aim of this project was to identify the causal and quantitative impact of measures designed to increase voluntary private savings in Mexico. Data included in the analysis span from early 2013 to mid-2016. For this project, the IDB partnered with Mexico’s National Commission of the Retirement Savings System (CONSAR) and 7-Eleven stores in the country.

Behavioral Analysis

Behavioral Barriers

Short-termism: The tendency to opt for a lesser benefit in the short term over a greater benefit in the longer term. It is associated with a preference for instant gratification. In this context, people might prefer spending US$100 today instead of spending US$110 after a few years of saving.

Over-optimism: Optimism bias makes us underestimate the probability of negative events and overestimate the probability of positive events. People often underestimate potential risks in the future, such as diseases, accidents, or losing jobs, for which they might need to save now to have a cushion in the future.

Hassle factors: We frequently do not act on our intentions because of small factors or inconveniences that hinder us or make the action uncomfortable. This could simply be the way in which the information is presented, the length of presentation, or that additional actions must be taken to execute a decision. In the case of private saving, the process to deposit savings might be too complicated and time-consuming.

Cognitive overload: The cognitive load is the amount of mental effort and memory used at a given moment in time. Overload is when the volume of information provided exceeds an individual's capacity to process it. We have limited amounts of attention and memory, which means we are not able to process all the information available all the time. Pension and saving systems are often complicated and might overload the cognitive capacity of citizens.

Behavioral Tools

Simplification: This involves reducing the effort required to perform an action by making the message clearer, cutting the number of steps or breaking down a complex goal into simple, easier steps. In this case, providing actionable steps and information about payment locations might simplify the deposit of savings.

Reminders: These may consist of an email, text messages, a letter, or a personal visit to remind the person making the decision about some aspect of their decision-action. These are aimed at mitigating procrastination, forgetfulness, and cognitive overload for those who must make the decisions. The implementation of a media campaign providing persuasive reminders to save provided an illustrative example.

Planning tools: Messages designed to encourage individuals to make a concrete plan for taking action. They urge the individual to divide the objective (for example, going to a medical appointment) into a series of smaller, concrete tasks (leave work early, find a babysitter, postpone a weekly meeting, etc.), and thereby anticipate unexpected developments. These often include a space for writing down crucial information such as the date, time, and place. In this case, the media campaign suggested concrete steps for savings (“10 pesos per day”).

Dual process theory: “Automatic” thought is known in the literature as system 1, while “controlled” thought is known as system 2. System 1 functions autonomously and quickly, without much mental effort and with apparently no voluntary control. System 2, on the other hand, is slower, controlled, and deliberative. It is used in mental activities requiring effort, including complex calculations. The reminders used in this study aimed for persuasion by using a jingle whose musical composition rather addressed system 1, while the content did so for system 2 (see also, Elaboration Likelihood Model).

Intervention Design

The study combined two common interventions to increase private, voluntary savings. One pillar of the intervention targeted transaction costs in the form of increasing locations for making deposits. From October 2014 onwards, voluntary savings were made available for a fixed, low fee at all 7-Eleven convenience stores by simply providing their national ID number. The second pillar urged workers to increase their voluntary savings with a national media campaign from July to December 2015 (see Figures 1 and 2); television ads in this campaign ads depicted the possibility of depositing savings at 7-Eleven stores. The hypothesized mechanism of the intervention was that combining the two pillars would have complementary effects in tackling two major impediments to voluntary savings at the same time.

The data for the analysis provided by CONSAR were anonymized at the account-level and covered the period from January 2013 to July 2016. Individual characteristics such as gender and age were observed. Out of a population of 19 million active worker accounts with CONSAR, those accounts with at least one voluntary contribution between 2013 and 2016 and consistent file data were selected (n=195,811). In later stages of analysis, they were split between those who had made a deposit before the intervention (“early savers”) and during the intervention (“treatment savers”). Additionally, a random sample of non-contributing account holders was used in a difference-in-difference design, with one predictor for increased access (b1), one predictor for the combination of access and media campaign (b2), and one predictor for the effect after the media campaign had ended (b3).

Data were collapsed to municipality-month level to be matched with geographical information on the presence of 7-Eleven stores. The analysis considered three outcomes:

- The total number of accounts with at least one voluntary contribution per municipality-month;

- The total number of voluntary contributions in a municipality-month; and

- The total amount of contribution in a municipality-month.

The fact that the people who did deposit savings were not all located in areas where 7-Eleven stores are present helped in the analysis to identify causal effects.

Figure 1. Spanish (original) and English Text of Media Campaign Jingle.

Figure 2. Images from Media Campaign Spots.

Challenges

- The difference-in-difference design assumes that the random sample drawn from those without voluntary savings during the period of observation was a good counterfactual to those who did deposit at least once a voluntary saving. The authors assume that unobserved preferences for saving are orthogonal (i.e., not highly related) to the presence of 7-Eleven stores.

- Causal identification might further be hampered by factors that confound effects. Besides 7-Eleven, two other localities started to accept voluntary savings, namely, Telecomm in June 2015 and Circle-K in February 2016. However, the high percentage of contribution via 7-Eleven and the media campaign’s focus on 7-Eleven makes confoundment unlikely.

Results

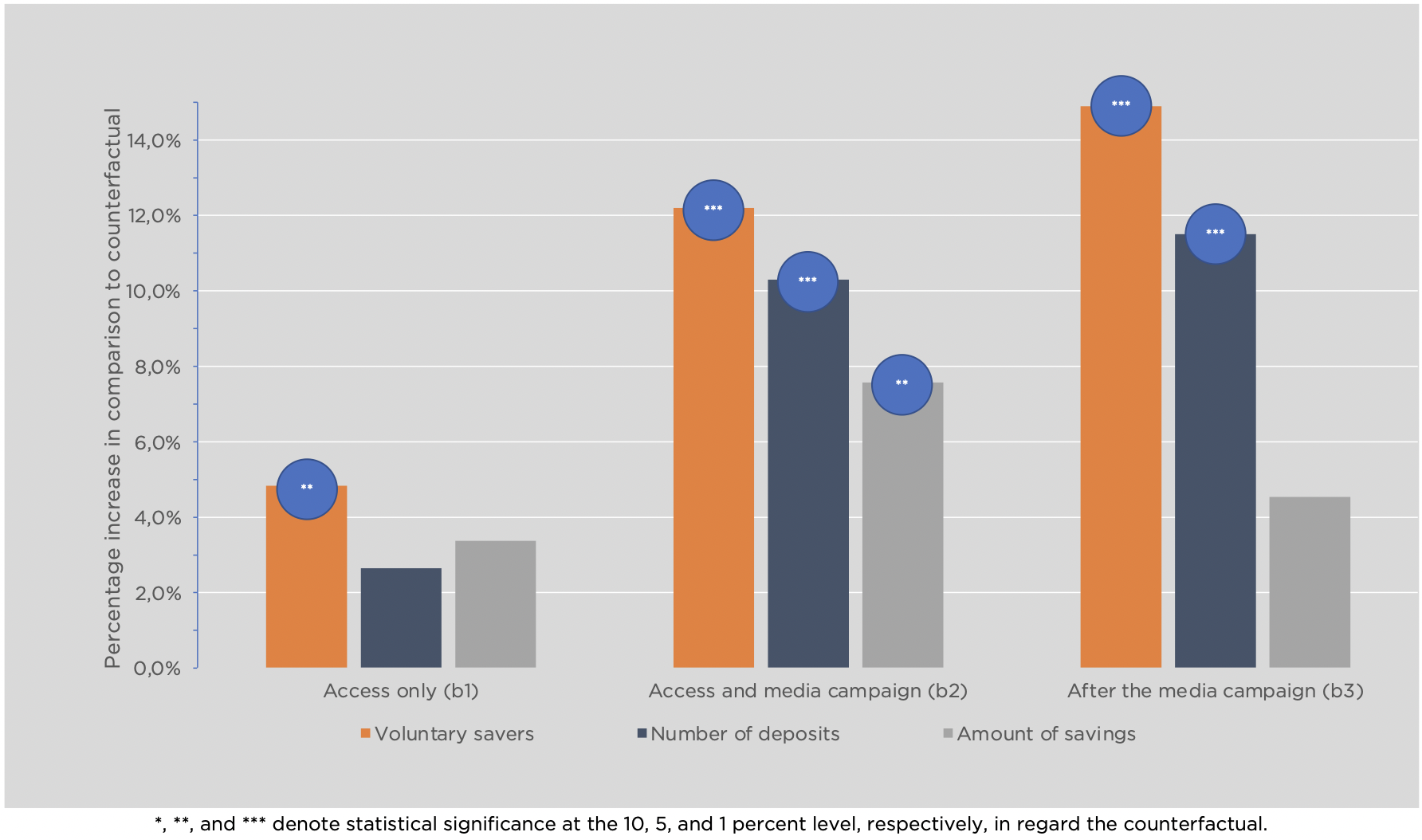

Results are presented for the three main outcomes: number of savers, the total amount of contributions, and the number of overall contributions (see Figure 3).

- First, municipalities with 7-Eleven stores showed a significant 5-percent increase in the number of voluntary savers before the media campaign, relative to those without 7-Eleven stores (b1). Second, during the campaign, the increase in number of savers reached 12 percent (b2). Third, For the months after the media campaign, there is a 15 percent increase in treated municipalities relative to the baseline (b3). Tests showed that all three coefficients are statistically different, which implies that the effect of the bundle of measures is larger than for the first measure focused on transaction costs alone.

- In regard to the total amount of contributions, the increase before the media campaign was insignificant (b1) but reached statistical significance for b2 and b3, with an increase of contributions during the campaign of 10 percent and after the campaign of 12 percent. Differences between the b2 and b3 are not statistically significant.

- The number of overall contributions increased by 8 percent during the campaign (b2), with the other coefficients before (b1) and after (b3) not reaching statistical significance. Overall, results indicate that the total amount of savings remained unchanged, implying that while more savings were deposited, their average amount decreased.

- Further analysis of underlying mechanisms suggest that the media campaign does not solely exercise an effect via the diffusion of information but also via the reminders and persuasive elements it contained.

Figure 3. Effects of Two Interventions to Increase Private Voluntary Savings in Mexico.

Policy Implications

- The study emphasized how well-planned policy interventions can have a significant and positive impact on saving behavior, thereby potentially alleviating major policy issues such as high rates of poverty among the elderly. It especially demonstrated how a bundle of initiatives can contribute to the formation of saving habits that are maintained after the intervention. However, future studies might further explore how to achieve an increase in the number of deposits without a reduction of the average deposit amount.

- The study suggests that complementary policies, such as those jointly tackling opportunity cost (accessibility) and behavioral barriers (reminders) seem to exercise a positive effect on saving behavior. For policymakers, the study underscores the value of observing more systemic interactions between structural and behavioral components to craft powerful solutions.