Altruism and Incentives to Reduce Teacher Sorting

Context

Education has the potential to provide equal opportunities for students from different backgrounds. Frequently, however, people from lower socioeconomic spheres receive a lower quality of instruction as a consequence of teacher sorting: the propensity of more highly qualified teachers to instruct students from a higher socioeconomic status, while less-qualified teachers are more likely to work in low-income schools.

This situation has significant adverse effects on students’ cognitive, non-cognitive, and long-term outcomes. Not surprisingly, it also contributes to inequality in Latin America. It is therefore important to explore policies that alleviate sorting patterns in order to offer high-quality instruction independent of students’ backgrounds.

The Project

Often, disadvantaged schools are understaffed and have low-quality instructors. Thus, this project addressed the need to explore policies that efficiently provide high-quality instruction in disadvantaged schools. The study used an experimental design integrated into Peru’s national teacher selection process in 2019. Specifically, the project – informed by behavioral sciences – implemented two interventions. One invoked an altruistic identity, and a second made pre-existing external incentives for teaching in disadvantaged schools more salient and comprehensible.

Behavioral Analysis

Behavioral Barriers

Cognitive overload: The cognitive load is the amount of mental effort and memory used at a given moment in time. The “overload” happens when the volume of information provided exceeds an individual's capacity to process it. We have limited amounts of attention and memory, which means we are not able to process all the information available. In this context, the process of registering one’s school priorities might be overly complex and may miss highlighting relevant information.

Hassle factors: We frequently do not act on our intentions because of small factors or inconveniences that hinder us or make the action uncomfortable. This could simply be the way in which the information is presented, the length of presentation, or that additional actions must be taken to execute a decision. Previous studies indicate that the information on differential compensation for teachers is often complex, with too many pop-up windows in online sources.

Social norms: The unwritten rules governing behavior within a society. A distinction is drawn between “descriptive norms,” which describe the way in which individuals tend to behave (for example, “many teachers work in disadvantaged schools”), and “prescriptive norms,” which establish what is considered acceptable or desired behavior, independent of how individuals actually behave (“Please contribute your part and teach in disadvantaged schools”). In this case, injunctive norms might motivate teachers to choose disadvantaged schools.

Other Barriers

Other factors encompass gender differences in regard to work flexibility and mobility, such as limitations associated with long commutes to remote areas, which disproportionately affect women and decrease their likelihood of teaching in disadvantaged schools.

Behavioral Tools

Simplification: Reducing the effort required to perform an action by making the message clearer, cutting the number of steps or breaking down into simple, easier steps a complex goal. In this case, the information on the benefits of working in disadvantaged schools was simplified and made easier to access.

Salience: Our attention is limited. Therefore, behavioral economics pays special attention to the moment when a message is delivered, the location in which it is delivered, and the content it emphasizes. Making key elements visible and prominent at the proper time and place are key tools, and just as important as the central content of the message itself. This study employed iconographies and colors to make information on disadvantaged schools more prominent.

Reminders: These may consist of consist of an email, text messages, a letter, or a personal visit to remind the person making the decision about some aspect of their decision-action. These are aimed at mitigating procrastination, forgetfulness, and cognitive overload for those who must make the decisions. Here, teacher candidates received messages to remind them of their upcoming decision and, depending on the experimental condition, of the rewards associated with disadvantaged schools.

Identity Priming: Priming is a phenomenon in which exposure to one stimulus influences how a person responds to a subsequent, related stimulus. These stimuli are often conceptually related words or images. Self-identity provides an individual a sense of one’s self, based on own physical characteristics, memories, experiences, relationships, group memberships, and values. In this realm, teachers might identify with pro-social values, increasing the likelihood of their opting for disadvantaged schools.

Intervention Design

The intervention used administrative data from the 2019 public school teacher selection process in Peru, including every region except the metropolitan area of Lima and the Constitutional Province of Callao, covering 86 percent of all teachers applying. In total, the experiment initially included 11,568 teacher candidates who successfully passed the Peruvian national teacher selection (out of over 180,000 applicants). The final sample consisted of 7,217 participants.

The study observed two outcomes from the online vacancy selection platform where candidates select and apply for particular schools: i) their choice of a disadvantaged school and; ii) a variable indicating if a candidate was assigned to a disadvantaged school for the final in-person evaluation.

The research design contained three arms with similar numbers of participants: one control group and two experimental groups, one employing an identity-related intervention, another an intervention based on extrinsic motivation. With this design, the experiment tests two mechanisms that are often described as successful in influencing decision-making.

The experiment took place between August and September 2019 and included three elements of intervention: (1) text messages, (2) a voluntary online exercise, and pop-ups (3). The first one was sent in the days before the online procedure for selecting schools, while (2) and (3) took place during the procedure:

(1) Text messages in the identity arm employed primes for altruistic identities, such as “Thank you for being an agent of social change.” Text messages in the extrinsic motivation arm emphasized benefits in monetary and career terms. Text messages in the control condition were neutral and provided basic information about the state of the application process.

(2) All three conditions offered a voluntary written online exercise during the application process. The identity-related exercise aimed to activate an altruistic identity, asking applicants to share reasons why they want to become a teacher. The extrinsic motivation exercise asked to reflect on how monetary incentives promote welfare of teachers. The control group was asked to complete an evaluation of the registration process so far.

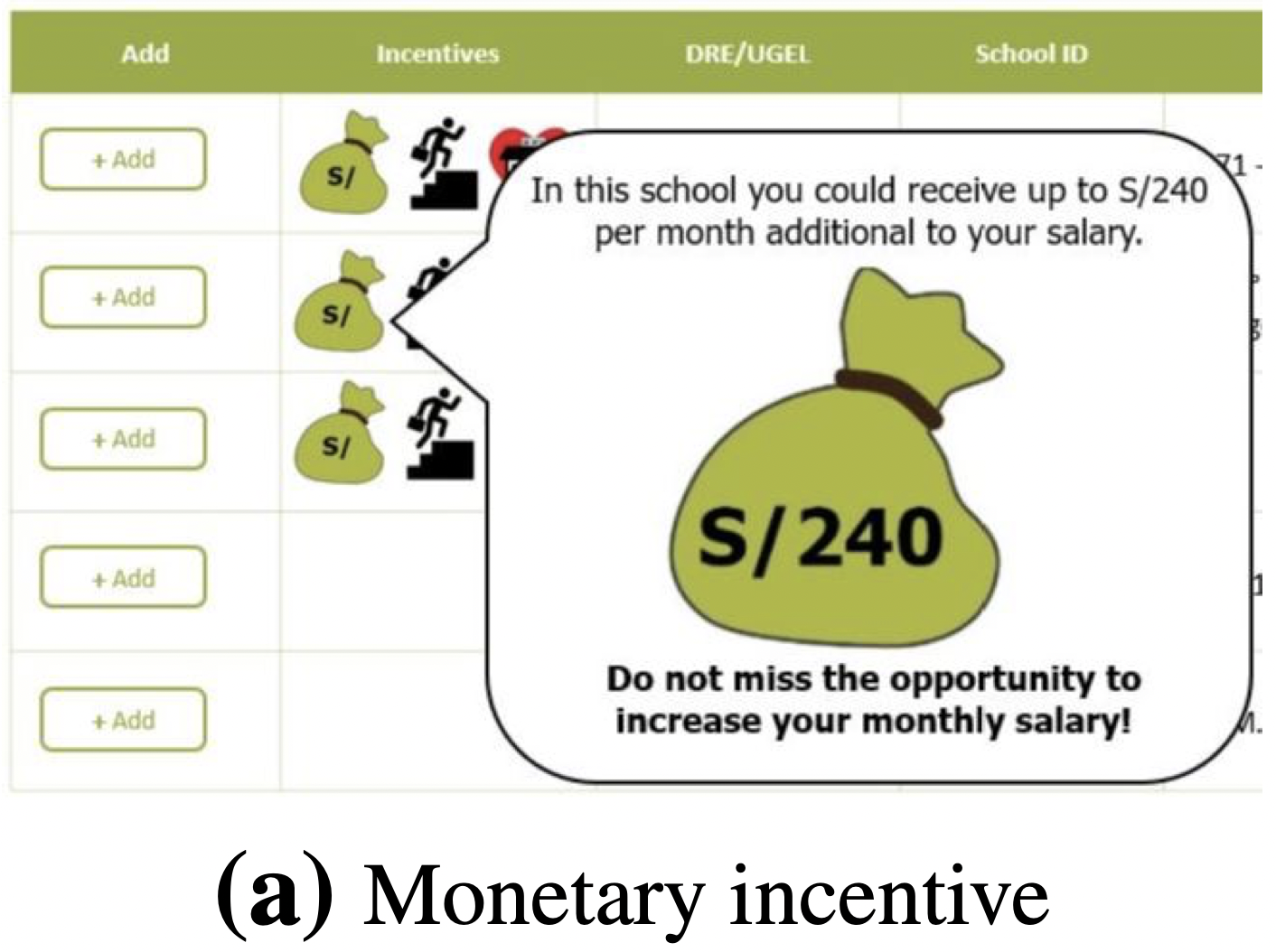

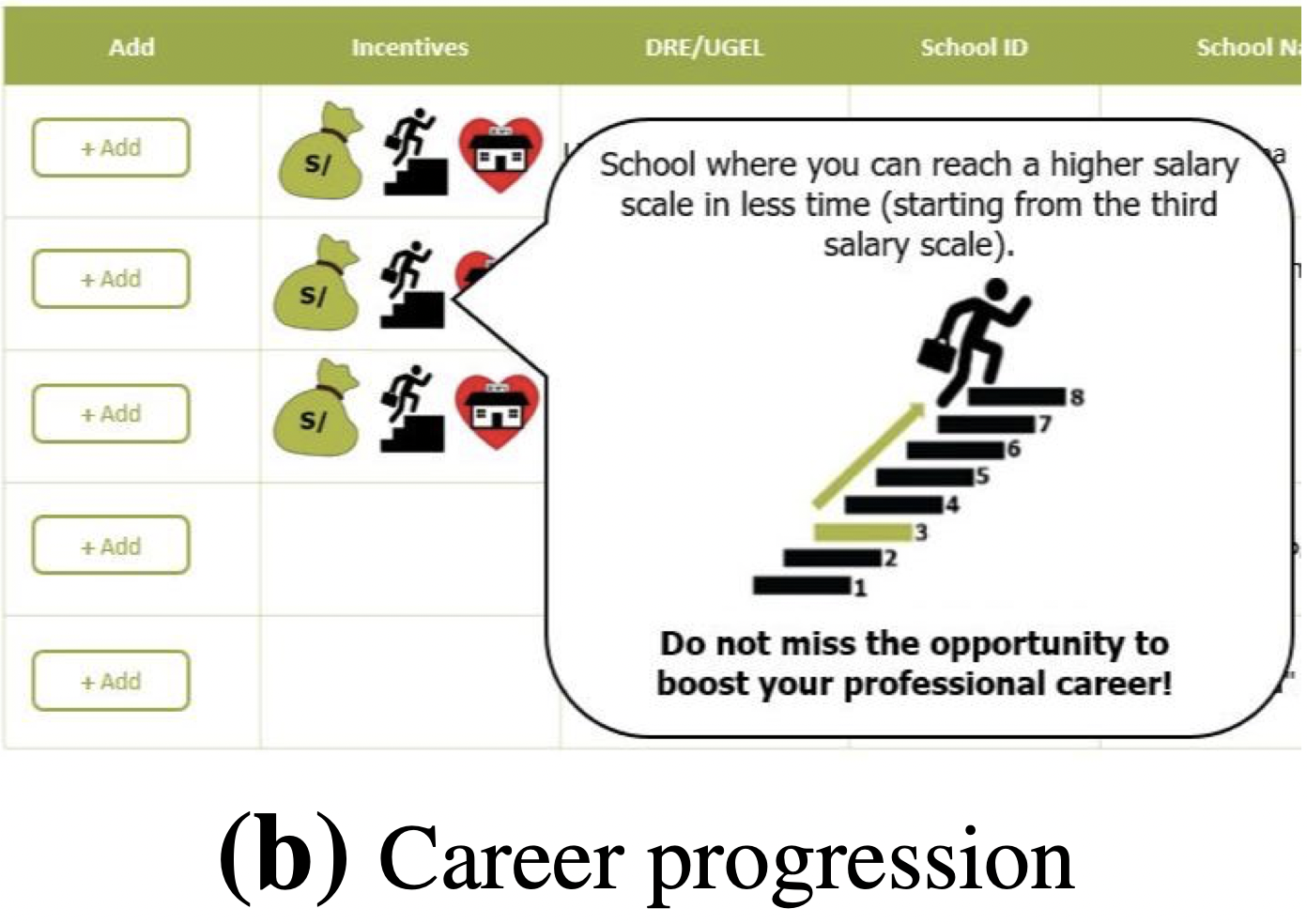

(3) During the online application process, all conditions contained pop-ups that appeared when candidates moved their cursors over icons (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Pop-up during Online Vacancy Selection: Identity Condition (translation).

Figure 2. Pop-up during Online Vacancy Selection: Extrinsic Motivation Condition (translation).

Challenges

- Some of the regions did not provide for sufficient variations of type of schools, such that successful teacher candidates from these regions had to be excluded from the sample.

Results

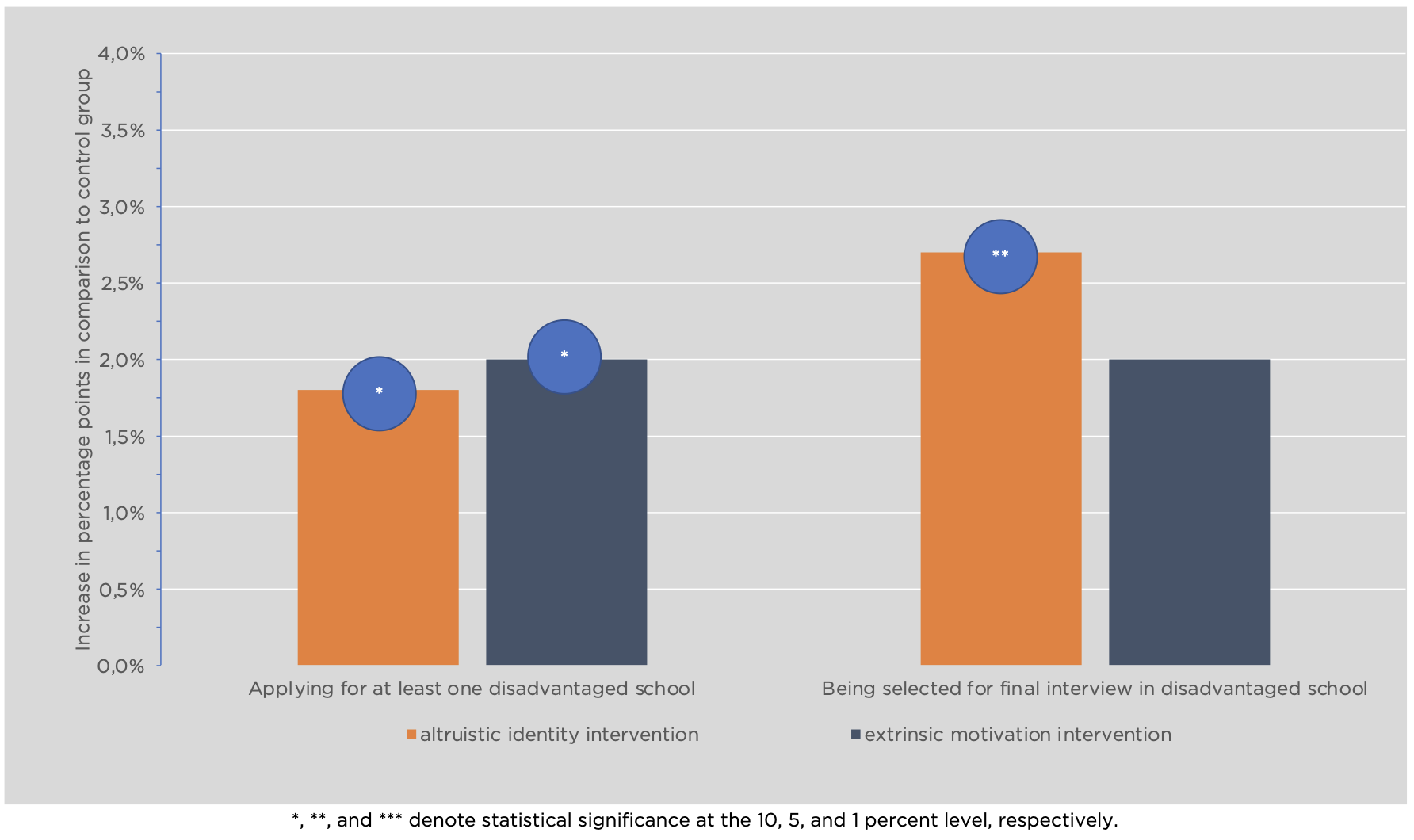

- Results indicate that both interventions have significant, positive effects on the probability of applying to at least one disadvantaged school (Figure 4). While the identity-related intervention led to an increase of 1.8 percentage points (pp), the extrinsic motivation condition led to an increase of 2 percentage points (both significant at the 10-percent level). There are also important differential effects. First, male and female teachers seem to have systematically different preferences for schools, with men being more likely to teach in poorer and remote regions. Second, “high-performing” candidates within the sample are more likely to select disadvantaged schools in the identity-related condition (2.8 pp at the 10-percent level), while “low-performing” candidates are more strongly reacting to the extrinsic motivation (2.4 pp at the 10-percent level).

- In regard to assignment for the final interview, the identity-based conditions led to an increase of assignment likelihood of 2.7 pp (5-percent level). While results indicate the group-level result might be driven by male and high-performing teachers, these interaction terms lack statistical significance. Effects on the extrinsic motivation group displayed a positive coefficient but equally lacked statistical significance.

- The authors estimate that the average cost of filling one vacancy in a disadvantaged school through either of the two strategies employed in the study is approximately US $13.

Figure 4. Treatment Effects of the Two Experimental Groups on School Selection and Assignment.

Policy Implications

- Given the importance of equal opportunities in numerous education systems, the study provides a cost-efficient tool to alleviate the effects of teacher sorting.

- The study provided evidence that identity-based interventions have particular potential to alter decision-making processes to foster selection of disadvantaged schools.

- The study design seems to be replicable since many countries use online selection vacancy selection portals.