Attracting teachers to disadvantaged schools in Ecuador by simplifying the application process

Context

A pressing matter in many Latin American countries is the difficulty of attracting teacher candidates to hard-to-staff schools, which are typically located in more remote and vulnerable areas. This problem in turn has a negative impact on educational outcomes, as low-performing students are more likely to attend hard-to-staff schools with less-qualified teachers. At the same time, some governments have adopted centralized application procedures where teacher candidates can apply to their preferred schools to work in a permanent, stable position in the public education system. These application procedures are vital in organizing candidates’ preferences and help allocate positions based on those preferences, but they often result in teacher sorting. At the end of the process, some schools receive more applications than available vacancies, while others struggle to attract applicants, generating sub-optimal outcomes to both teacher candidates who are unable to secure a job and schools that are unable to attract candidates. While governments’ efforts remain insufficient to mitigate teacher sorting and its accompanying congestions and inefficiencies, this situation provides an opportunity for testing behavioral science tools to motivate teacher candidates to apply to hard-to-staff schools.

The project

The authors partnered with Ecuador’s Ministry of Education to design and implement a behavioral intervention to attract teacher candidates to hard-to-staff schools to reduce teacher sorting and market congestion around socioeconomically advantaged schools. The intervention involved changes to the official application procedure in which candidates see a list of schools with available vacancies and then select their preferred options. The changes exploit the order effects of presenting some options first in candidates’ listed preferences for schools. In this case, the application system listed hard-to-staff schools either first or in alphabetical order. The intervention took place in November 2019 during the sixth round of the centralized teacher selection process called Quiero Ser Maestro (I Want to Become a Teacher, abbreviated QSM).

Behavioral Barriers

Hassle factors: We frequently do not act on our intentions because of small factors or inconveniences that hinder us or make us uncomfortable. This could simply be how the information is presented, its length, or additional actions to execute a decision. In this context, teacher candidates might not select a hard-to-staff school among their preferred schools because they might fail to identify these schools in the many pages that comprise the list of available vacancies.

Cognitive overload: Cognitive load is the amount of mental effort and memory used at a given moment in time. Overload occurs when the volume of information provided exceeds an individual's capacity to process it. We have limited amounts of attention and memory, which means we are not able to process all the information available. In this case, there is plenty of information about each school (its location, the number of vacancies offered by the school, and the number of applicants for each vacancy at the time of the candidate’s entry on the platform), and several schools are listed on the same page, making it very difficult to identify special cases like hard-to-staff schools.

Behavioral tools

Simplification: Reducing the effort required to perform an action by making the message clearer, decreasing the number of steps involved or breaking down a complex goal into simple steps. In this case, two contextual factors were used. The first was a graphic identifier of hard-to-staff schools (an icon next to the school’s name), and the second was presenting the options in a specific order to make sure hard-to-staff schools were visible to the candidates.

Intervention design

The team partnered with the government of Ecuador to attract teacher candidates to hard-to-staff schools. Their designs aimed to ease the problems generated by teacher sorting, where some congestion is generated in advantaged schools and severe shortages of teachers are seen in disadvantaged schools that often fail to attract higher-quality professionals. This project was built on the Ecuadorian national teacher selection process during 2019.

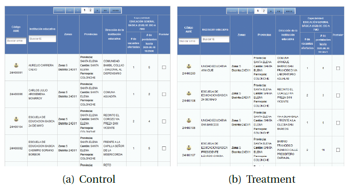

The intervention involved 18,133 candidates who were randomly assigned to either a control group (C) or treatment group (T). Both groups had access to the same list of vacancies and relevant information about schools with job openings. The only difference between the treatment and control groups was that the system listed hard-to-staff schools first for candidates in the treatment group, whereas schools were displayed in alphabetical order in the control group. Hard-to-staff schools had an icon highlighting their potential for higher teacher impact, and this icon was visible to both control and treatment groups.

The teacher selection process had three phases: eligibility, merits and public examination, and application. In the eligibility phase, candidates must pass a psychometric test and a knowledge test specific to their specialty. Candidates had to pass the tests in the first phase (with a score of at least 70 percent in the knowledge test) in order to reach the second phase. In the second phase, candidates are evaluated according to their academic and professional credentials and according to their performance in giving a mock class. Candidates must score at least 70 percent on the mock class to proceed with their application to job vacancies. In the third phase, eligible candidates apply for school vacancies on an online platform. Since this is the phase where the intervention took place, the candidates in both the treatment and control group were high performers who had successfully passed the tests in the first and the second phase. After the three phases, candidates were assigned to a vacancy by an algorithm that considers candidates’ scores in the second phase as well as their ranked preference for vacancies.

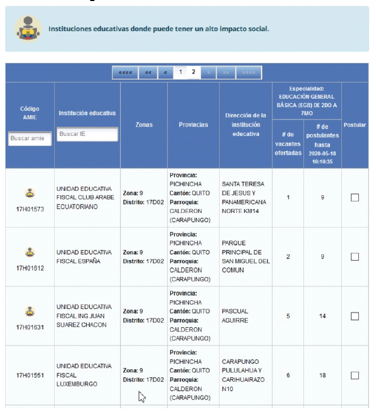

Teachers had seven days (November 18-24, 2019) to apply for a vacancy on the online platform. They first had to select the area where they wished to search for vacancies (a province, city, and county). The system would then show all job vacancies available for them, and candidates could select up to five vacancies of their choice. At this stage, available vacancies were listed in alphabetical order for the control group and hard-to-staff schools were listed first for the treatment group (see Figure 1). The list of options showed basic information about each school: its location, the number of vacancies offered by the school, and the number of applicants for each vacancy at the time of the candidate’s entry on the platform. Once teachers finished their selection, the system listed all the selected vacancies on a final screen, allowing teachers to list the vacancies in their preferred order. Teachers were given an opportunity to re-enter the system and change their original selection within a four-day validation period.

Figure 1. Platform Screenshot – School list

In order to identify the mechanisms behind the plausible order effects of the treatment, an online survey including measures of attention and altruism was administered to all teacher candidates in the evaluation sample. The online survey was sent by the Ministry of Education to candidates’ email addresses throughout the month of September 2020, with weekly reminders to those who had not yet responded. Only 56 percent responded to the survey.

As the goal of this behavioral intervention was to attract candidates to hard-to-staff schools, the main outcomes used to measure the effects of the intervention were the following: the percentage of hard-to-staff schools in candidates’ choice set; whether their first choice was a hard-to-staff school; whether their first two choices included a hard-to-staff school; and whether their first three choices included a hard-to-staff school.

Challenges

The main challenge with an online tool is that not all the users assigned to the treatment are exposed to it because exposure depends on whether users’ selections lead to choices displaying the treatment information. In this case, teacher candidates had to select the area where they wished to search for vacancies in order to see which ones were available. Given this pre-selected feature (the area), some teachers could only apply to a single vacancy, whereas others found their options consisted exclusively of hard-to-staff schools or included no hard-to-staff schools.

Results

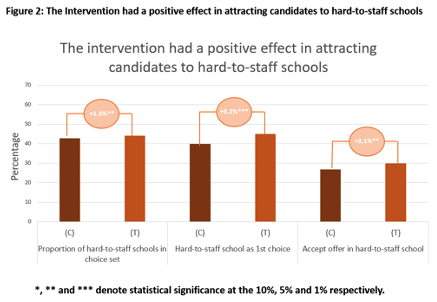

Listing hard-to-staff schools first in the list of available vacancies had positive effects on attracting teacher candidates to these schools (see Figure 2).

- The proportion of hard-to-staff schools was 1.4 percentage points (pp) higher in the choice sets of candidates whose list started with hard-to-staff schools (T) compared to candidates whose lists were in alphabetical order (C).

- Candidates whose list started with hard-to-staff schools (T) were 5.2 pp more likely to rank a hard-to-staff school as their first choice (2.7 pp more likely to rank them among the first two choices and 2.9 pp more likely to rank them among the first three choices) compared to candidates whose lists were in alphabetical order (C).

- Candidates whose list started with hard-to-staff schools (T) were 3.1 pp more likely to accept a teaching position in a hard-to-staff school compared to candidates whose lists were in alphabetical order (C).

- The evidence from the survey suggests that the identified order effects of listing hard-to-staff schools first were not generated by cognitive skills, inattention, or a different level of altruism. Instead, the evidence suggests that choice overload may have played a relevant role.

Policy Implications

Given that teachers have short- and long-term effects on students’ educational outcomes, especially among the most vulnerable students, finding a solution for teachers sorting into teaching positions is a significant concern for policymakers.

This project implements a zero-cost behavioral intervention exploiting order effects that contribute to reducing teacher sorting in Ecuador, providing an essential tool for governments addressing the same issue. Given the evidence gathered from this intervention, tools like providing different sorting options prioritizing hard-to-staff schools in the list of available vacancies to teacher candidates can be developed for and with governments in Latin America and the Caribbean as a way of complementing other policies designed to attract high-performing teachers to hard-to-staff schools.