Can Rewards Improve Tax Compliance?

Context

As both behavioral and tax compliance studies show, the success of a reward is not independent of its design. Some rewards seem to backfire by crowding out intrinsic motivations, and when they do work, their effect does not last long. Moreover, many rewards seem to affect only the intended recipient and have few if any spillover effects on other individuals. As rewards increasingly become an instrument used by policy makers, it is important to find a mechanism that does not crowd out intrinsic motivation, is long lasting, and has positive spillover effects on third parties.

The Project

A policy innovation introduced by the municipality of Santa Fe, Argentina, allowed us to evaluate different mechanisms for rewarding tax compliance—participation in a lottery (financial motive), public recognition (moral channel), and provision of a visible and durable good (reciprocity and peer effect channels).

In an effort to reward good taxpayers and improve property tax compliance, the municipal government of Santa Fe in January 2009 organized a lottery that entitled winners to the full construction or renovation of the sidewalk in front of their home. The city announced a lottery for those with no pending tax arrears at a future date. After the due date, the city government randomly selected 400 individuals among the more than 72,000 taxpayers who had paid their property tax. Lottery winners were announced in local newspapers, and these individuals were awarded the construction of a sidewalk where possible.

Behavioral Analysis

Behavioral Barriers

Prescriptive norms: These refer to what society approves or disapproves of—that is, what is considered to be right or wrong—regardless of how individuals actually behave. Such norms are useful for reaffirming or encouraging what are considered positive individual behaviors while discouraging negative ones. In the context of our study, the acceptable behavior is to pay taxes when they are due to the government. In the context of our study, the acceptable behavior is to pay taxes when they are due to the government.

Present bias: It is the tendency to choose a smaller gain in the present over a large gain in the future. It is related to the preference for immediate gratification. It is also known as hyperbolic discounting. People with such a bias might value present gratification more than greater benefits in the future—for example, they might avoid paying taxes even when there is a possibility of winning a lottery.

Behavioral Tools

Signaling: The act of conveying credible information to others about one’s expected actions or behavior.

Moral suasion: The act of persuading a person or group to act in a certain way through theoretical appeals, persuasion, or implicit and explicit threats.

Intervention Design

In an effort to reward good taxpayers and improve property tax compliance, in January 2009, the municipal government of Santa Fe organized a lottery (called “Premio al Buen Contribuyente”), that entitled winners to the construction or renovation of a sidewalk outside their home. The prize had an additional purpose, to showcase a “model” sidewalk.

Lottery rules were straightforward. Owners of residential units, commercial properties, and/or vacant lots were eligible to participate in the lottery as long as they had paid their 2008 property tax liabilities by January 12, 2009. Each eligible property received a unique number, and 400 properties were randomly chosen from a set of 72,742. The lottery took place on February 27, 2009. City officials contacted each of the winners and also announced lottery results in local newspapers.

Challenges

The sidewalk renovations included the removal of any old sidewalk already present, sewerage adjustments, and convenient features such as a trash receptacle that would not be accessible to animals, as well as a section dedicated to plants and trees (also provided by the municipality).

Renovating the sidewalks was expensive. The city estimated that the average sidewalk renovation would cost Arg$5,250 (approx. $1,553) (Decree 1716). This is equivalent to 14.4 times the average yearly tax payment (Arg$363.5) in 2008, and 9.7 times the average yearly tax payment of 2009 (Arg$539.5).

Results

Results indicate that rewarding taxpayers for good behavior has large positive and persistent effects on lottery winners and their neighbors.

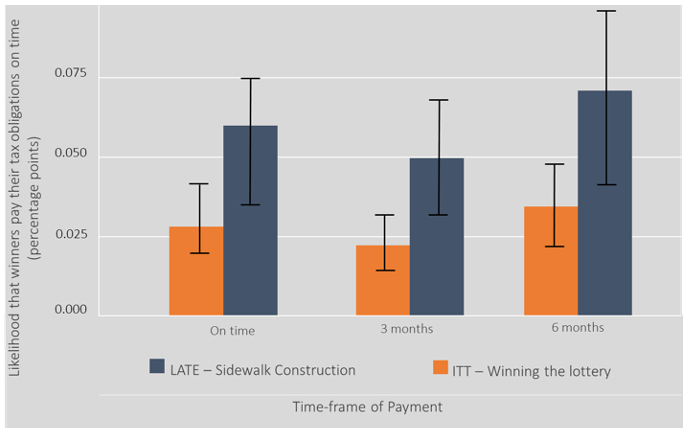

The lottery increased the likelihood that winners paid their tax obligations on time by about 3.1 percentage points (as an average over the period), and it raised the probability that property taxes were paid within three to six months by 2.4 (2.1) percentage points (see ITT columns in figure 1). Lottery winners were also 3 percentage points more likely to continue paying on time over the next few years compared to their peers. This effect was significant (p<0.05) and persistent at least three years after the intervention. Not every lottery winner actually received the sidewalk construction prize; in such cases, the effect of the lottery win and public recognition faded away after a few months. Completed sidewalk renovations increased timely payment rates by 7.1 percentage points (average effect for the whole period), and the likelihood that tax bills were paid within three to six months by 5.5 and 4.8 percentage points, respectively (see LATE columns in figure 1), an effect that persisted over time.

Figure 1. Effect of Intervention on Share of Payments Made

High and persistent spillover effects from winners to their neighbors were found. These effects are not universal but seem to depend on the salience of the reward. As an example, a homeowner who was the neighbor of a winner but did not participate in the lottery, and was living in an area of the city with low public service provision, was about 7.5 percentage points more likely to pay on time (p<0.05), about 10 (15) percentage points more likely to pay within 3 (6) months (p<0.01) and about 15 percentage points more likely to pay at all (p<0.0.1). These results are persistent in the long run. No significant financial motive effect was found, indicating that people did not pay their taxes just to participate in the lottery.

Policy Implications

- The findings provide evidence of intervention features that make a positive inducement more successful, whether for tax compliance or other policy purposes.

- Durable, high-visibility rewards may help to crowd in intrinsic motivation and have positive spillover effects on third parties.