Chasing Informality: Evidence from Increasing Enforcement in Large Firms in Peru

Context

Peru's labor market, much like those in other developing countries, is marked by a high level of informality. Approximately 10 million workers in Peru are classified as informal, lacking Social Security registration and, consequently, access to benefits such as health insurance and pensions. Despite recent improvements in Peru’s national labor inspection system, Peru only has 0.2 labor inspectors for every 10,000 workers, which in effect allows workers and firms to continue operating informally. The pervasive informality in the labor market leads to lower productivity, reduced tax revenues, and inadequate worker protection.

This study addresses the challenge of informality by analyzing the impact of an increase in firms’ perception of greater oversight on labor formalization.

Project

The project, conducted between October 2017 and January 2018, aimed to address labor informality by increasing the perception of enforcement among large formal firms in Peru. The study involved randomly sending one of two letters to firms. Letter one followed a deterrence approach and emphasized that non-compliance with labor requirements is a serious offense punishable by a substantial fine. Letter two alternatively outlined the benefits of formalization, including the positive impact it can have on increasing firm productivity. The project employed a rigorous empirical approach, utilizing data from administrative records and firm-level surveys to measure the impact of enforcement actions on firms' formal employment practices post-treatment.

Behavioral Barriers:

Lack of Information: People may lack relevant information, for instance, because information is difficult to obtain, scarce, or hard to understand. In this context, many firms and workers may not be fully aware of the benefits of formal employment or the risks associated with non-compliance.

Limited attention: Even when the relevant information is in principle available, people’s ability to process information is limited. As a result, they may ignore relevant pieces of information unless they are saliently communicated.

Risk Aversion: Firms may be risk averse in that they have a preference for a sure outcome or the status quo as opposed to changes. Specifically, firms in Peru may be accustomed to operating informally and may be hesitant to change due to fear of increased scrutiny, increased costs due to formalization, or potential legal issues.

Behavioral Tools

Information: Frequently, the target population does not have the information needed to make a decision, and providing the information is sufficient to nudge people into a decision and consequently undertaking a beneficial action. As a result, educating firms about the benefits of formal employment and the risks of non-compliance may result in greater uptake of formal labor practices.

Enforcement as a Nudge: Using inspections and fines as a deterrent to encourage compliance with labor laws.

Design

The study uses data from firms and workers registered with the Peruvian tax authority (SUNAT) through the electronic payroll system (Planilla Electrónica), which includes all formal firms, both public and private.

To increase the perception that the authority will enforce compliance with social security, SUNAFIL sent letters to firms, randomly dividing them into three groups: 348 firms received a deterrence letter, 349 firms received a social norms letter, and 348 firms formed the control group and received no letter. The structure of the letters was identical except for the main treatment message. The deterrence letter emphasized the severe consequences of non-compliance, including fines and back-due contributions, while the social norms letter highlighted the benefits of formalization, such as protection against health risks and potential productivity gains. The letters invited firms to review the status of workers on the electronic payroll and were personalized, addressed to the firm's legal name, and signed by a SUNAFIL government official.

The study implemented a Randomized Controlled Trial method to evaluate the impact of the letters, measuring the effect by comparing the average difference in the number of formal workers between the treatment groups (firms receiving either type of letter) and the control group (firms receiving no letter) using a difference-in-difference estimation. The primary objective is to measure the impact of the letters on the firm’s perception of the likelihood of oversight in law enforcement. In other words, if, after receiving the letter, the firm considers that it is more likely to be monitored, this should be reflected in greater legal compliance.

Challenges

The project faced issues with attrition and non-compliance, as post-treatment data were not available for some firms and some letters were not successfully delivered. These issues did not undermine the empirical strategy or the conclusions drawn.

- Sending letters to firms significantly increased the number of formalized workers. The average number of formal workers increased by almost 12 for the combined treatment (both letters), with the effect being greater when the letters contained deterrence messages (increased by 20 workers on average, as compared to an insignificant 3-worker increase observed with the social norm treatment.). Conclusively, deterrence letters, which highlighted the costs of fines for non-compliance, were more effective than letters emphasizing the benefits of formalization. Firms reacted more strongly to the increased perception of the likelihood of being audited and the associated costs of punishment.

- Treatment effects are heterogenous based on firm size. The effect of the deterrence letter is led by large firms, which on average have almost 65 additional formal workers after the intervention. While the social norms letter likewise had a greater impact on these firms, that impact was insignificant.

- There is evidence of job creation among firms in the deterrence treatment group compared to the same month of the previous year. In other words, these firms have a higher number of formalized workers, either because new hires exceed separations, or because existing workers were formalized after receiving the letter.

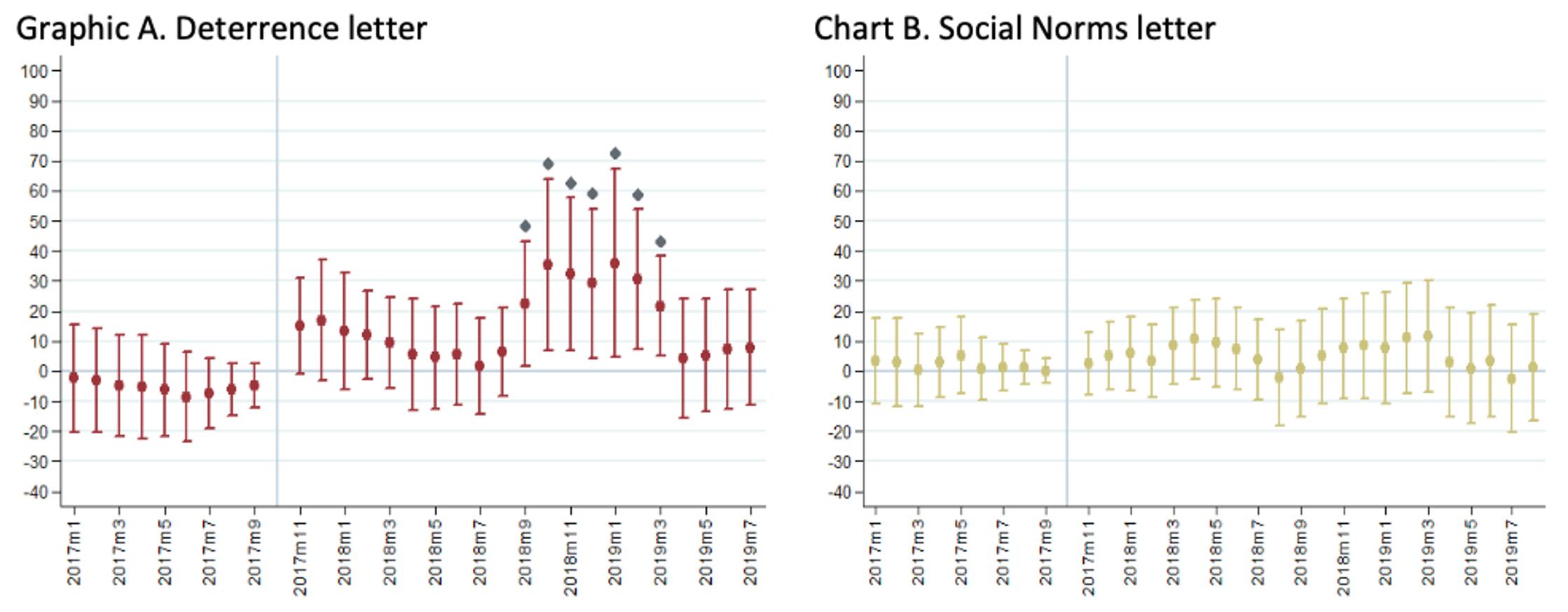

- As shown in Graphic A, the deterrence letter had a positive average effect but was not significant in the month following the intervention. A signficant difference between the control group was observed between September 2018 and March 2019, underpinning the long-term effects of the intervention

- As shown in Chart B, the social norms letter did not have a statistically significant effect in any of the months following the intervention.

- The intervention was cost-effective, with the collection of social security contributions exceeding the unit costs of sending the letters. Each letter had a unit cost of PEN 30.4 (USD 9.3), while an in-person inspection cost PEN 1,309 (USD 409) in 2018.

Policy Implications

- The use of letters as a low-cost intervention can be an effective complement to traditional labor inspections, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

- Policies should ensure that the perceived likelihood of monitoring is backed by actual enforcement actions to maintain the credibility and effectiveness of deterrent messages.

- Implementing information technologies to send electronic notifications can expand the reach of enforcement efforts while keeping costs low.

- Emphasizing the costs of non-compliance and the likelihood of audits can be more effective than highlighting the benefits of compliance. This finding can guide the design of future enforcement communications.