Combating COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Behaviorally informed campaigns in the Caribbean

Context

Increasing vaccination uptake and understanding the drivers underlying COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy are vital to curbing the COVID-19 pandemic. In the Americas, ten out of the thirteen countries that haven’t yet reached the WHO’s vaccination target are in the Caribbean. Those countries include Belize and Barbados. The government of Belize, for example, had COVID-19 vaccines available for 110% of the eligible population in February 2022, but at that time only 60% had received at least one dose. While several possibilities exist, the literature in this area suggests vaccine hesitancy could be caused by limited access to resources and information, and by socio-cultural rejection issues.

To understand this phenomenon in Belize, at the end of 2021 the IDB conducted a national household survey, which pointed to fear of side effects and lack of trust in vaccines as some of the main reasons for not receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. As a follow-up to this survey, a series of behaviorally informed Facebook communication campaigns was implemented with the objective of increasing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and uptake. The findings from these studies can guide policymakers and health authorities in designing and implementing future vaccination campaigns.

Project

To gain insight into the drivers behind vaccine intention, uptake, and hesitancy in Belize, the IDB implemented a national household survey representative of the population 15 years and older, which reached over 1,250 members of the population. The survey was based on the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction (IMBP), which asserts that factors such as attitudes, perceived norms, and perceived behavioral control influence a person’s intention to behave in a certain way. The survey included questions related to vaccination intention, demographic factors, beliefs, attitudes, and perceived norms. From this sample, 20.7% of the participants declared that they had not been vaccinated and, among this group, 65.4% showed some degree of hesitancy.

As a follow-up to this survey, the IDB partnered with the Belizean Ministry of Health and Wellness to launch a series of five behaviorally informed Facebook campaigns to boost COVID-19 vaccine uptake. These campaigns were directed at the entire population of Belizean Facebook users (260,000, which is more than half of the total Belizean population).

Behavioral barriers

Vaccine hesitancy: refers to refusing or postponing vaccination despite having access to vaccines and services.

Availability heuristic: individuals tend to estimate the probability of a future event based on how readily representative examples of such an event come to mind.

Hassle factors: seemingly small inconveniences, such as having to read a lot of information or take an extra small step to complete an action, can hinder or disrupt decision-making processes.

Loss aversion: is the cognitive bias that leads individuals to experience losses more intensely than equivalent gains.

Overconfidence: is the tendency to overestimate or exaggerate our own capacity to perform a certain task.

Behavioral tools

Descriptive social norms: these norms describe how a social group behaves, without regard for whether the behavior is good or bad. Presenting norms can help change behavior.

Framing effects: the way that information is presented influences behavior.

Intervention design

The objective of the Facebook campaigns was to test the effectiveness of sequentially displayed messages related to the following five topics.

- Vaccine safety. The message sent in this campaign was: "It's safe. Hundreds of thousands of Belizeans have taken the vaccine and are protected. What are you waiting for?"

- Effectiveness. The message sent in this campaign was: "It's effective. Once vaccinated, you are less likely to catch COVID, less likely to be hospitalized, less likely to die. What are you waiting for?"

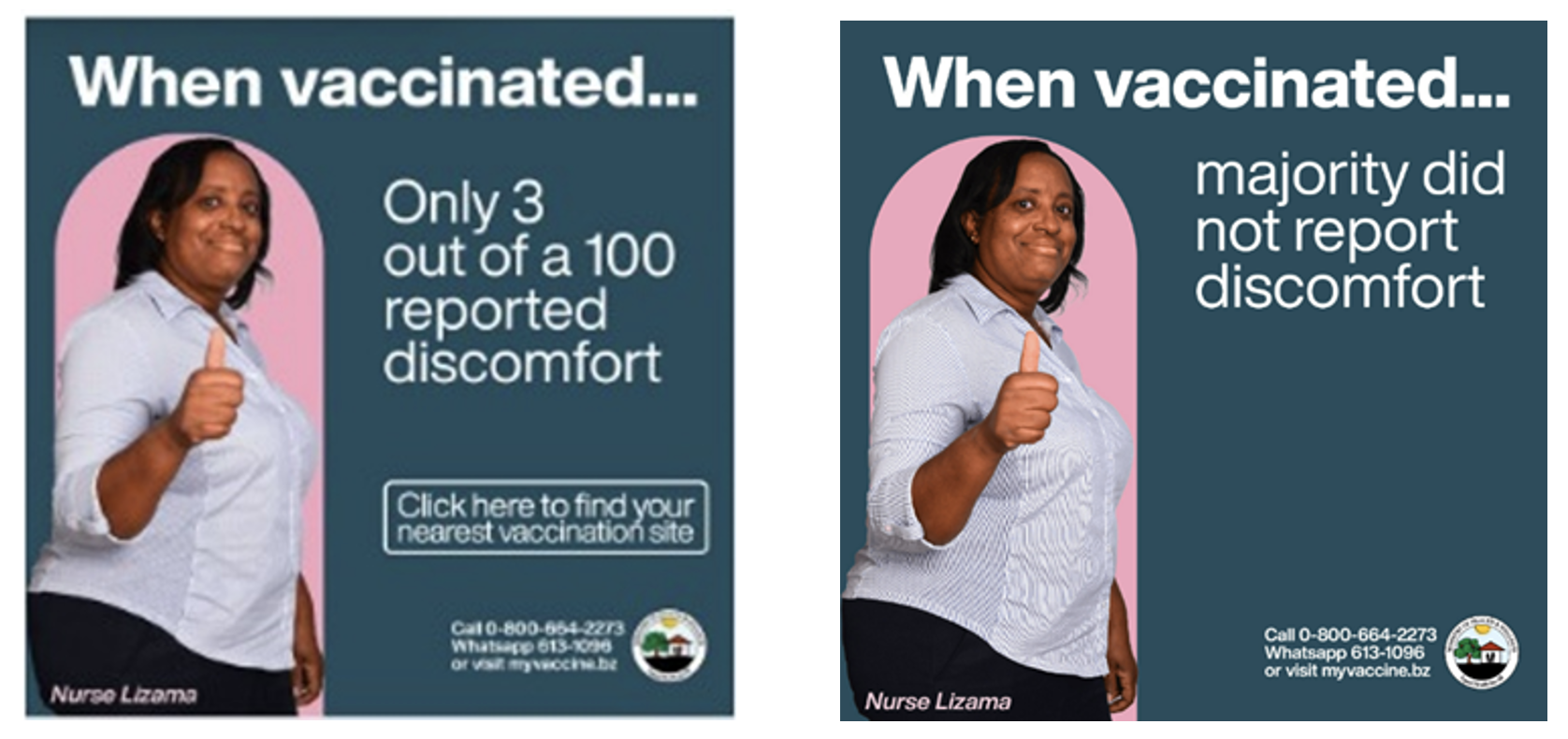

- Side effects. The messages sent in this campaign were: "When vaccinated... only 3 out of 100 reported discomfort”; “When vaccinated… few people have discomfort”; and “When vaccinated… the majority didn’t have discomfort."

- Self-protection. The message sent in this campaign was: "Are you protected? Vaccination helps protect you and your family."

- Child vaccination. The message sent in this campaign was: "Children can now get a COVID-19 vaccine."

To decrease the misperception of the lack of vaccine accessibility, all the messages included the sentence "Click here to find your nearest vaccination site" at the end. For each of the five campaigns, the analysis tested their association with higher vaccination uptake and with engagement with official information about vaccines and the vaccination process in Belize.

As a second step, for the campaign that displayed messages related to side effects, an AB test experiment targeted at the same universe of Belizean Facebook users was implemented. The Facebook AB Testing tool is a randomized experiment where two or more versions of a campaign are shown to random and mutually exclusive groups to determine which version performs best. In this context, this tool was used to test different ways of presenting information about COVID-19 side effects and their effect on engagement with official information about vaccines and the vaccination process in Belize. Users were randomized into one of the following three messages (an example of which can be seen in Figure 1): "When vaccinated... only 3 out of 100 reported discomfort”; “When vaccinated… few people have discomfort”; and “When vaccinated… the majority didn’t have discomfort").

Figure 1: Facebook campaign with embedded AB test

Source: Idealab Studios Digital Marketing.

Challenges

- Given the urgency to allocate the vaccines, the Ministry of Health and Wellness decided to advertise the Facebook campaigns sequentially without an experimental design in mind. For this reason, the analysis doesn’t include causal claims linking the different campaigns to Facebook-related measures ("Clicks" and "Engagements") or the uptake of vaccines.

- Even though the Facebook AB split testing feature was used to run an experiment, the effects of this experiment could only be tested on Facebook-related measures. This is because Facebook data were measured at the individual level, while the data on vaccination rates were measured at the district level.

- There might be contamination from different information sources, given that there were several activities taking place at the same time of the campaigns. These include graphic and in-person campaigns in households, community hospitals, elderly centers, schools, and public advertisements on social media, local TV (talk shows), and local radios.

Results

The survey implemented in Belize showed that, among the 65.4% of the unvaccinated who expressed vaccine hesitancy, the fear of side effects, low trust in the vaccines, and doubts about vaccine efficacy were among the top reasons for not getting a COVID-19 vaccine. This study also showed that the reasons that could motivate the unvaccinated to get the vaccine included protecting their own health and those of others as well as being able to resume social activities and work.

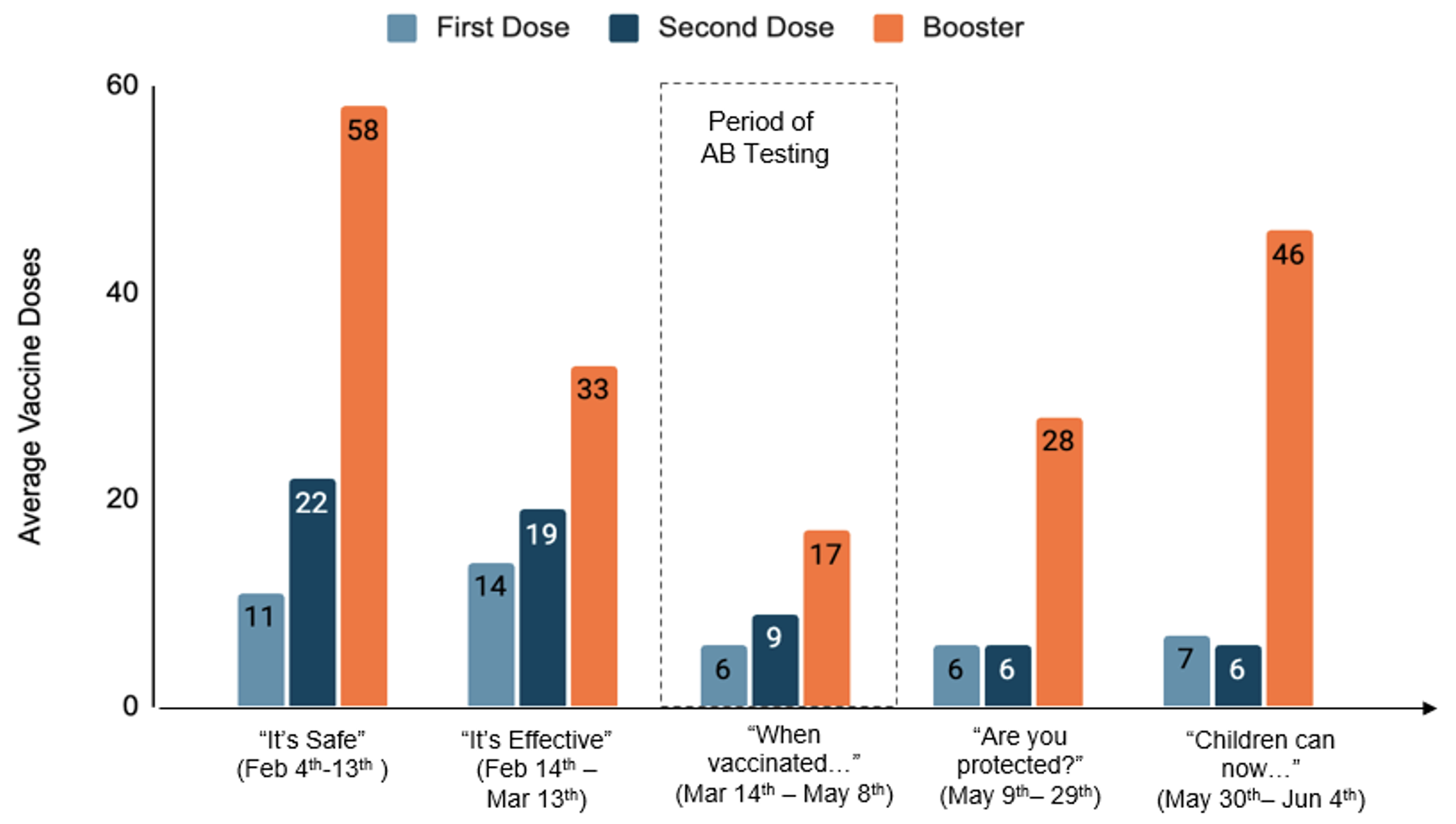

The Facebook campaigns showed that increasing public trust in the COVID-19 vaccine by highlighting its safety was the best predictor for getting the second and booster doses of the vaccine (see Figure 2, which shows the average vaccine doses applied in the period within each campaign). In particular, the “It’s safe” campaign was found to be associated with 11, 22, and 58 additional first, second, and booster shots, respectively. This is a relevant finding, given that the campaign was run only for nine days (February 4 to February 13, 2022) and the cost was almost zero. Figure 2 also shows the much higher impact of the campaigns on booster shots, a meaningful result as they were run in early 2022 when boosters were only starting to be rolled out. The campaign announcing that children were eligible for vaccines drove the most engagement, perhaps due to perceptions of safety and novelty of the news.

Figure 2: Average daily vaccine doses achieved by type of FB campaign

The AB test embedded in the campaign that shared information about side effects showed that a positive frame (“When vaccinated… the majority didn’t have discomfort"), which implies presenting the information with a positive connotation, rather than the use of probabilities ("When vaccinated... only 3 out of 100 reported discomfort”), was more effective at driving engagement with the campaign and encouraging people to get more information.

The results from these studies were later leveraged in Barbados to design a social media campaign called “Easy Vaxx” and an informational platform to promote COVID-19 vaccination. Both the campaign and the platform included persuasive messaging that addressed the hesitancy factors identified in the population of this country.

Policy implications

- Protecting one's own health and that of others remains the most important reason for vaccinating against COVID-19.

- Addressing the population’s most pressing concerns regarding the vaccine could potentially encourage people to get vaccinated.

- Understanding citizens’ concerns regarding a health issue can help develop more effective campaigns to encourage a particular behavior involving this issue.

- The framing of a message in a positive way can be more effective than framing it negatively, especially in health-related matters.