Effect of a Social Norm Feedback Program on the Unnecessary Prescription of Nimodipine

Context

The frequent over-prescription of drugs without supporting evidence for their use has turned into a major public health issue. The resulting polypharmacy (i.e., use of multiple prescription drugs) among elderly patients and the adverse effects of continued drug use represent a burden on the health system without providing benefits to patients. In Argentina, up to 45 percent of drugs prescribed for cognitive impairment are not recommended. Among them, nimodipine is the most frequently used. Thus, there is a need to explore ways to reduce non-recommended prescriptions to improve patient’s health and alleviate health systems stressed by high operational costs.

The Project

In the past, various strategies have been tested to reduce non-recommended prescriptions, such as increasing awareness via education. However, many of these strategies are expensive and have not proven to be highly efficient. In contrast, behavioral interventions such as nudges have demonstrated a high potential for low-cost effectiveness in many policy domains. Using a randomized-control trial, this project tested a behaviorally-informed intervention to reduce the prescription of nimodipine within the National Institute of Social Service for Retired and Pensioners (INSSJP-PAMI), which provides free medical care to older Argentinians. Conducted mainly in 2019, the study tested if emails including a social norm intervention improved prescription practices by physicians. It also assessed participants’ perception of the intervention after its completion.

Behavioral Analysis

Behavioral Barriers

Social norms: The unwritten rules governing behavior within a society. A distinction is drawn between “descriptive norms,” which describe the way in which individuals tend to behave (for example, “most people arrive on time”), and “prescriptive norms,” which establish what is considered acceptable or desired behavior, independent of how individuals actually behave (“Please arrive on time”). In this case, physicians might see that their colleagues prescribe nimodipine frequently and might thereby feel confirmed in their prescription practices.

Status quo bias: Our tendency to maintain the current status of things. This current status, or status quo, is used as a reference point, and any change with regard to this point is seen as a loss. Physicians might be used to prescribing nimodipine and are reluctant to adopt different treatments.

Overconfidence: Also called superiority bias. This is the tendency to overestimate or exaggerate one’s own capacity to perform a certain task. In this context, physicians might overestimate their knowledge of the efficiency and side effects of nimodipine.

Over-optimism: Optimism bias makes us underestimate the probability of negative events and overestimate the probability of positive events. For instance, physicians might underestimate possible side effects of the drug and overestimate its potential benefits for the patients.

Behavioral Tools

Descriptive norms: These describe how a social group behaves, without regard for whether the behavior is good or bad. Presenting them can help change behavior. For example, one physician might think that everyone prescribes the drug as frequently as he / she does, when in reality the majority of colleagues do so less frequently. In that case, presenting the descriptive norm that most physicians prescribe the drug less than oneself can improve individual behavior.

Feedback: It is an effective tool to enhance awareness of the consequences of various choices. It may fill knowledge gaps and foster the search for efficient alternatives. For instance, physicians might receive information on how frequently they prescribe the drug compared to the medically approved standard.

Reminders: These may consist of an email, text messages, a letter, or a personal visit to remind the person making the decision about some aspect of their decision-action. Reminders are aimed at mitigating procrastination, forgetfulness, and cognitive overload for those who must make the decisions. Physicians, for example, might receive a reminder of the potential risks of prescribing a drug.

Intervention Design

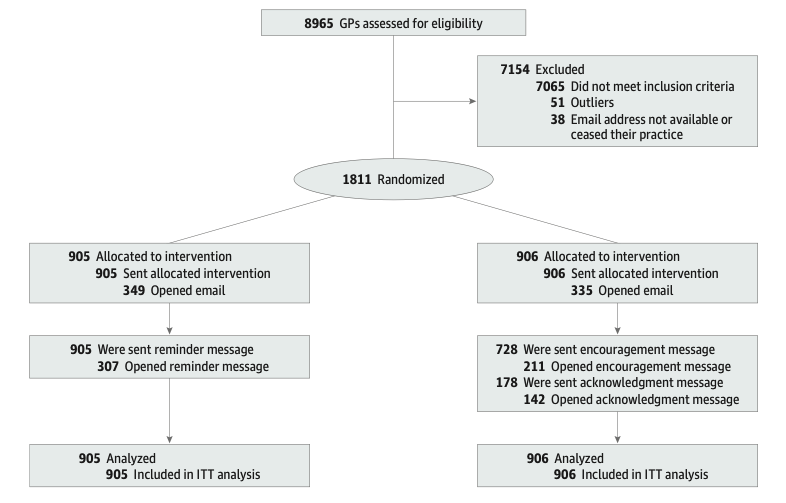

The study was conducted with 1,811 physicians within the INSSJP-PAMI system who were part of the top quartile of nimodipine prescriptions (Figure 1). Physicians were randomly allocated to the treatment or control group. The main dependent variable was the physician’s ratio of nimodipine to all prescriptions. After assessing the baseline for one year, the intervention period extended from May to October 2019.

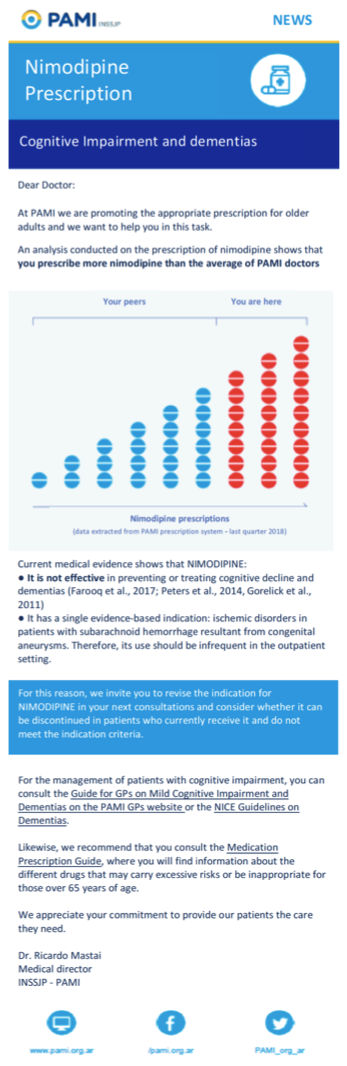

Both groups received two emails each framed as part of a communications campaign for improving pharmacological practice quality. The treatment group’s first email included information on the correct use of nimodipine and a comparison of the physician’s number of prescriptions relative to their peers (Figure 2). It thereby employed the use of social norms and feedback. The second email, sent three months after the first, also included information on the drug’s correct use. Additionally, it provided feedback on prescription changes: the email to physicians who reduced their prescriptions of nimodipine by 10 percent or more included a component that acknowledged their progress, while those who did meet the target received a component that encouraged them to change their practices (see pubication). Participants in the control group obtained two emails at the same moments as the treatment group, one containing information on unnecessary drug prescription and polypharmacy in older adults, and another including information on informing about risks of benzodiazepines for older patients.

In designing the intervention for the treatment group, wording was carefully selected in order to focus the intervention on the descriptive norm component instead of inducing a deterrence effect often used by regulatory authorities.

After the intervention was completed, individuals in the treatment group received an anonymous, voluntary survey to learn about their perceptions of the intervention.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Study Recruitment.

Figure 2. First Email Sent to Individuals in the Treatment Group.

Challenges

- The intervention only targeted those physicians who were part of the top quartile of nimodipine prescribers. Thus, it is difficult to generalize the findings for physicians in the lower three quartiles.

- The rate of unopened emails in the treatment group was relatively high (around 60 percent for email 1, and 20 and 70 percent, respectively, for the two versions of email 2).

- Interactions between the treatment and the control group might have taken place, which would confound the effect of the treatment.

- The study could not control for whether physicians used a different non-recommended drug instead of nimodipine. Similarly, long-term effects of the intervention could not be investigated with this research design.

Results

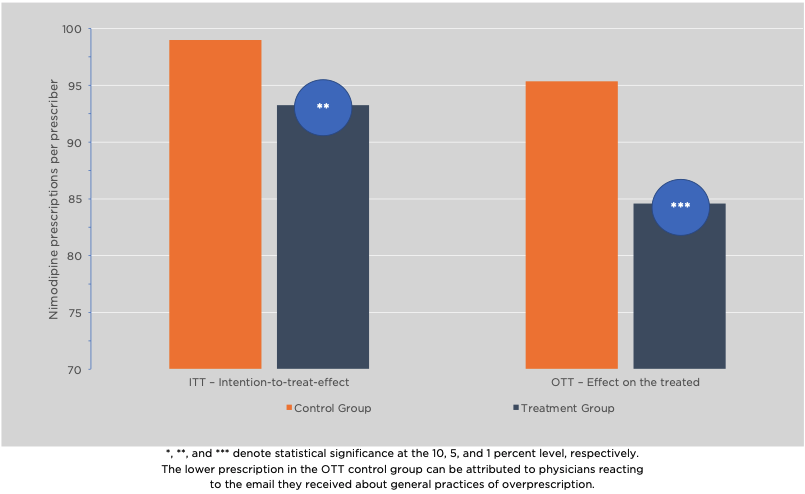

- Results indicate that the social norm intervention led to a statistically significant and meaningful reduction of 5.7 percent of nimodipine prescriptions compared to the control group (ITT), as shown in Figure 3.

- Looking at subgroup effects, physicians who opened either the first or the second email in the treatment group prescribed 11.1 percent less nimodipine units.

- Cost-benefit analysis reveal that the expenditures for the treatment group were approximately 7 percent lower than for the control group. Extrapolating the savings for all physicians in the country for one year, this would amount to approximately US$ 235,000.

- The post-intervention survey revealed that physicians who read the emails considered them useful and encouraged them to modify their prescription behavior. In particular, more than nine out of ten of those completing the survey considered the information on over-prescription and polypharmacy as important; more than four-fifths did so for the information on the scientific evidence, while close to three-quarters did so for the social comparison information.

Figure 3. Nimodipine Prescriptions in Control and Treatment Groups.

Policy Implications

- In this study, emails containing a behaviorally-informed intervention served as a cost-efficient tool to reduce the prescription of non-recommended drugs for cognitive impairment.

- Descriptive norms, feedback, and reminders proved themselves to be important tools for policy interventions in the health sector.

- Policymakers might explore ways to increase the uptake of information sent via email to further increase the efficiency of email-based interventions.