How to improve participation in tsunami drills in Ecuador

CONTEXT

Following the earthquake in Indonesia in 2004 and the tsunami it caused, countries have begun recognizing the need to implement Early Warning Systems (EWSs). An efficient EWS includes four elements: (i) awareness of disaster risks; (ii) detection of danger; (iii) communications; and (iv) preparations to react appropriately. In the case of Ecuador, the 2016 earthquake pushed the implementation of an EWS for tsunamis along the country’s coast. Based on knowledge about tsunamis along the Pacific coast, it installed sensors, communications systems, and warning sirens in coastal towns. The objective of the EWS is to avoid the loss of human life in an area with a population of close to 2 million. The project is financed through an IDB loan (code EC-L1221).

For this system to be effective, the participation of the at-risk communities is essential. One of the most common exercises to test community preparedness levels is evacuation drills, although, unfortunately, the entire population does not participate in them. Although EWS instruments and mechanisms were optimal from a technical point of view, behavioral barriers affect citizen response and often lead them not to participate. Therefore, the behavioral barriers in citizens' minds must be analyzed to devise strategies for encouraging them to get involved.

THE PROJECT

The IDB’s Disaster Risk Management department and Behavioral Economics Group, in coordination with Ecuadorian authorities, tested the use of text messages designed using behavioral science to increase participation in the Tsunami evacuation drills in five of Ecuador’s coastal municipalities. The municipalities comprising the experimental sample were Atacames, Jama, Sucre, Manta, and Santa Elena. The project was executed between October 2020 and February 2022. The text messages were sent in October 2021.

BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS

Lack of Information: People may lack the information they need for a variety of reasons, including difficulty finding it, an absence of information, or because it is difficult to understand. In Ecuador, residents did not know the time and date of the drills. The survey found that only 21% “strongly agreed” that they knew this information. They also did not know exactly what to do when the EWS siren sounded: only 39% said they were “very sure” what to do in this case.

Scarcity mindset: This refers to the feeling of not having enough resources (financial or time, for example). These in turn absorb some of the finite cognitive resources—known as “mental bandwidth”—that people have, limiting their capacity to make good decisions. It could be argued that the residents of Ecuador generally know the details of the drills but later forget them because other life priorities consume the majority of their cognitive resources.

Status quo bias: This is people's tendency to maintain the current status of things, which is used as a point of reference. Any change in this regard is perceived as a loss. It should also be noted that despite having information about the drills, residents assume not participating as the predetermined option or habitual point of reference and persist with this attitude due to inertia.

Social norms: The series of unwritten rules governing behavior within a society. A distinction is drawn between “descriptive social norms,” which focus on how people tend to behave, and "prescriptive social norms," which establish what is considered acceptable or desirable behavior, regardless of how people act in reality. In this exercise, residents saw that participation among people in the community was low. Of the total sample, 38% of those who participated in the drill thought that participation in their community was low; for nonparticipants, 45% said they "strongly agreed" or "agreed" that they had not participated because their neighbors also did not participate.

Justification: This involves the granting of moral licenses. Self-justification is a cognitive bias that occurs when a person uses their earlier "good" behavior to justify later "bad" behavior, often without explicitly using this logic. The diagnosis found that of the total sample, the people who believed they were at greater risk of death in the event of a tsunami participated less in the drills. This appears to indicate that people justify not participating in the drill with the belief that, should a tsunami occur, evacuating would not save them.

BEHAVIORAL TOOLS

Information: This is the act of providing information to those who did not have it previously. In this exercise, information was provided on the time, day, and location of the drill.

Reminders: These can take the form of an email, a text message, a letter, or an in-person visit to someone who must decide on some aspects of their intention-action. Reminders are intended to mitigate procrastination, forgetfulness, and/or cognitive overload. In this exercise, regular reminders of the date and time of the drill were sent via text message and WhatsApp.

Framing: Given the tendency to draw different conclusions depending on how the information is presented, the desired options can be presented emphasizing the important part of the information. The positive or negative aspects of a decision can also be highlighted, leading to an option being perceived as more or less attractive. For this experiment, highly emotionally-charged text messages were sent urging people to prevent the deaths of their loved ones.

Descriptive social norms: Describe the behavior of a social group, regardless of whether it is good or bad. Disseminating these norms can help change behavior. The team in charge sent messages emphasizing that others in the community were participating in the drills.

Planning prompts: These messages are designed to invite individuals to make a concrete action plan. They urge people to divide the objective (for example, going to a medical appointment) into a series of smaller, concrete tasks (leave work early, find a babysitter, postpone a weekly meeting, etc.), and thereby anticipate unexpected developments. These often include a space for writing down crucial information such as the date, time, and place. The messages sent included a call to action clearly indicating that when the EWS siren sounded, they were to take the evacuation route to the safety zone.

INTERVENTION DESIGN

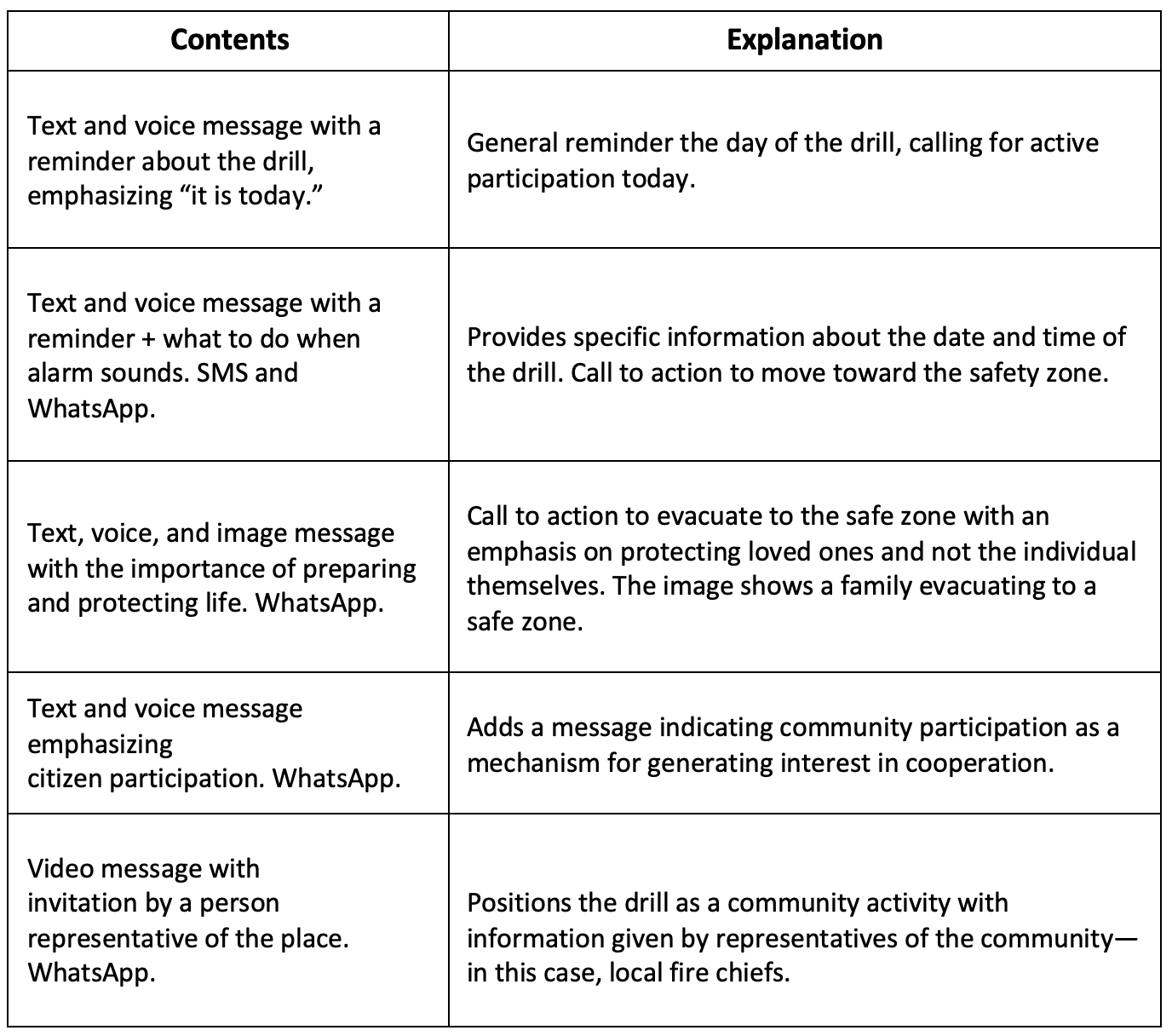

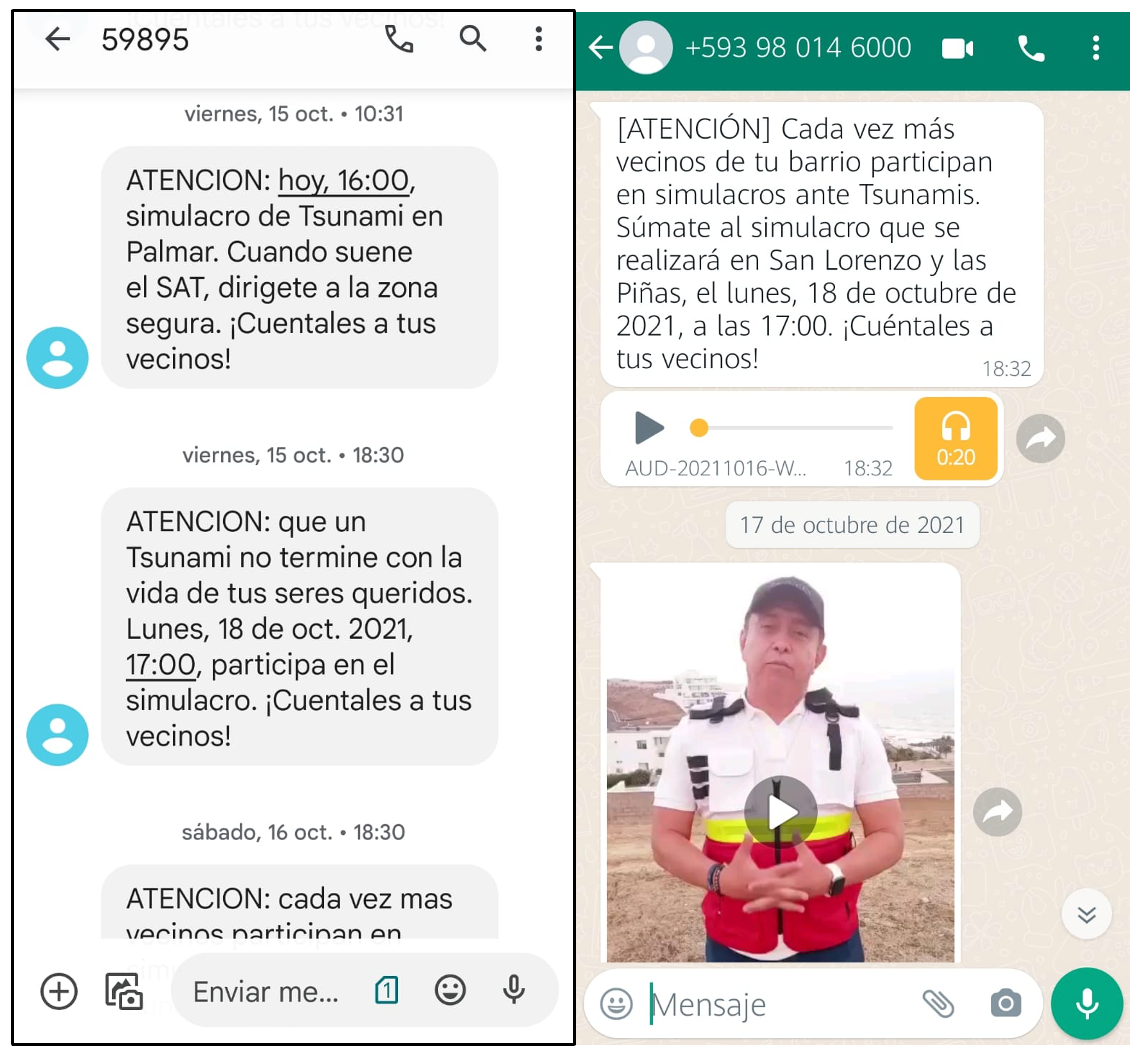

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of these messages, a randomized controlled trial was designed in the framework of official tsunami drills in five of Ecuador's coastal communities. The drills were conducted in October 2021. The experiment involved approximately 750 homes in these communities, located on 71 urban blocks selected randomly during the implementation of a baseline survey for which the cellular phone number of the adult who answered it was obtained. Those randomly assigned to the treatment group received the messages on their cell phones daily starting one week before the date set for the drill. Individuals randomly assigned to the control group did not receive any messages. The messages were prepared by the research team in charge of the study, with support from a specialist in social communication. They were sent through altiria.com and WhatsApp. These messages can be viewed in Table 1 and Figure 1.

It should be noted that the treatment group was subdivided into two groups. The first group only received informational messages reminding individuals on the date of the drill and what they were required to do when the alarm sounded. The second group received the full package of messages.

The effectiveness of the messages was measured objectively by registering individual participation in the drill. This was the responsibility of the volunteers in charge of the official evacuation points determined by the competent authority. Although objectively registering participation offers a significant advantage, it is possible that many individuals evacuated their homes and gathered at unofficial locations. This type of participation could not be documented in the October 2021 drills.

Table 1. Message content

Figure 1. Text messages and WhatsApp

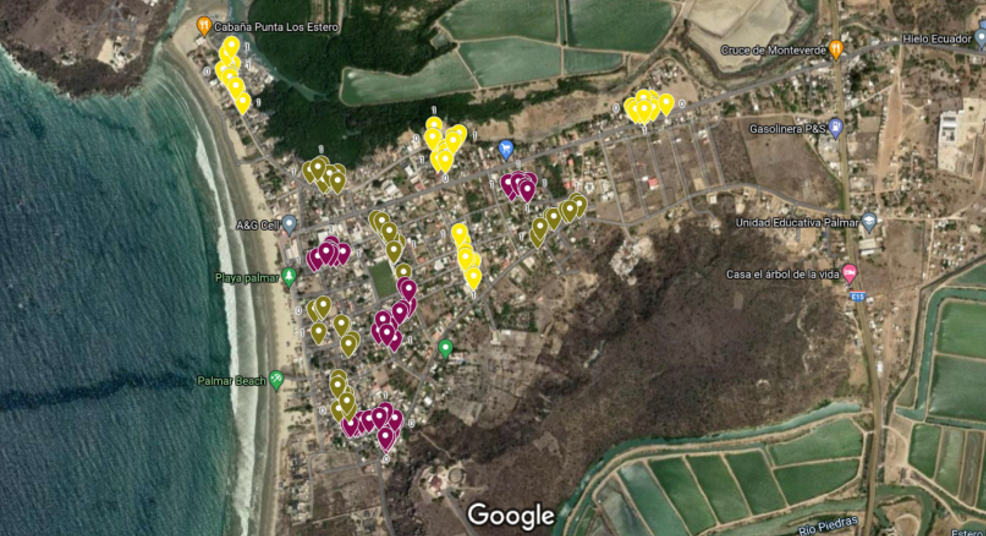

Allocation to a treatment group by block or neighborhood (figure 2), based on an average of 10 families per neighborhood. Within each community, two-thirds of the neighborhoods were assigned to the treatment group and the last third to the control group. As indicated above, the treatment group was subdivided into two groups. The total sample covers approximately 75 blocks, home to 750 families.

Figure 2. Example of randomization by block within a community

The design is therefore randomization by cluster or group, but within which individual outcomes are analyzed. The main outcome of interest is whether a family member evacuated to one of the safe zones established by the competent tsunami authority.

Follow-up telephone survey

In January 2022, an official tsunami warning was issued for Ecuador’s coast. In order to assess the responses of the individuals in the control and treatment groups to this event, a telephone survey was conducted in April 2022. For the survey, contact was made with 150 families initially included in the study.

CHALLENGES

- Unfortunately, different factors external to the design limited the scope of the intervention and, thus evaluation of the impacts of interest. Specifically, in two communities, the tsunami alarm was not activated at the right time. In one community, the local government did not promote the drill in any way (in that community, the participation was 0%).

- It should be noted that tsunami evacuation drills are usually organized for the educational community and employees of public institutions. For this reason, proposing a task for the community rather than institutions can confuse people since it goes against their expectations concerning how things have always been done.

- Lastly, the cost of personnel needed to keep track of participants in the drill was high.

Results

It was impossible to analyze the impact of using nudges to increase participation in tsunami drills. However, the data and information obtained from the investigation are very important for improving and understanding the EWS, so the experiences and data obtained here will be used by the National Risk and Emergency Service (SNGRE) of Ecuador for evacuation drills starting in 2022.

- In general, the rate of evacuation to official safe zones was minimal: less than 5% of the residents of all the communities evacuated to a safe zone

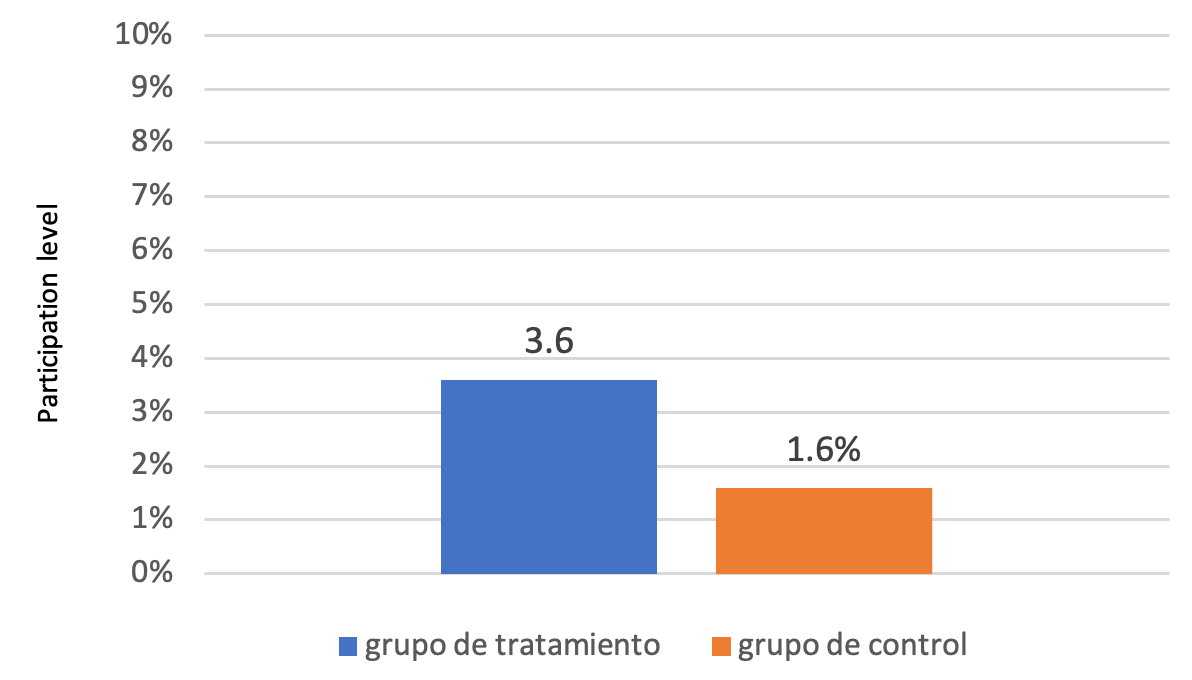

- Looking at the two communities where the alarm was activated on time and local government promoted the drill, only five individuals from the treatment group turned up on the registries prepared by the volunteers (3.6% of the total. Only one turned up from the control group (1.6% of the total). However, the difference between the groups is not significant (figure 3).

Figure 3. Level of participation in the drill considering only the two communities where it was carried out correctly

- Lastly, and as indicated above, it is possible that some individuals evacuated their homes and went to places other than the official sites. This participation could not be documented in the October drills.

- Comparing the baseline and the follow-up telephone survey of 2022 shown in figure 3, the individuals who were assigned to one of the treatment groups showed slightly higher participation than those assigned to the control group, although the difference was not significant.

- Results from the 2022 follow-up also suggest that individuals with lower education levels assigned to the treatment group were less likely to indicate that the tsunami drills were not useful.

- The fact that the decision was self-reported and the telephone survey sample was small are two significant limitations to interpreting the outcomes. However, they suggest participation in the drills must be evaluated more carefully, as it was not necessarily limited to evacuation to official sites, especially considering the diverse attributes of vulnerable populations.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The study found that efforts to review and improve disaster risk management (DRM) public policy using behavioral science offer a new potential approach for actors in Ecuador. This may also be the case for other countries in the region.

It was also found that for behavioral science to be effectively integrated into DRM, other aspects of DRM need to be improved at the same time. This includes, for example, better management of the participation history of those involved in evacuation drills (including their socio-economic characteristics), and better management of equipment like community sirens.

The experience left an additional lesson: Although the behavioral sciences are clearly understood in theory, it is important to amass some practical experience when it comes to applying them to large-scale public policy activities like evacuation drills at the national level. In this regard, the competent Ecuadorian authority (SNGRE) is in a position to enrich its experience by putting behavioral sciences and their teachings into practice. This point has very significant potential.