Incentives for Civil Servants. The Role of Behavioral Insights

Context

Good governance is seen as a pillar of democratic stability, economic growth, and welfare. For good governance, it is paramount to expand the capacities and increase the quality of the public sector. Well-functioning public sectors are equally important for a state’s legitimacy vis-à-vis its citizens. One step in this direction consists of increasing task compliance and efficiency by civil servants. While private sectors frequently rely on economic incentives to achieve such outcomes, there are several limitations to such an approach in the public sector. In consequence, it is important to explore alternatives.

The Project

From 2017 to 2019, the IDB conducted a project with the aim of exploring alternatives to economic incentives to increase task efficiency and compliance. The specific task to improve was civil servants’ compliance with requests under the Freedom of Information Act, which allows any person to obtain access to government records. This task serves as an excellent example because civil servants’ incentives to process the requests are relatively low compared to other tasks. It provides results of the effectiveness of a behavioral intervention and a traditional approach in form of a training program that was conducted by the city government.

Behavioral Analysis

Behavioral Barriers

Short-termism: The tendency to opt for a lesser benefit in the short term over a greater benefit in the longer term. This is associated with a preference for instant gratification. People might prefer focusing on easier, more convenient tasks in the moment even if they risk a larger penalty in the case of continued non-compliance with requests under the Freedom of Information Act.

Hassle factors: We frequently do not act on our intentions because of small factors or inconveniences that hinder us or make it uncomfortable. This could simply be the way in which the information is presented, the length of its presentation, or that additional actions must be taken to execute a decision. In the case of citizens’ requests, civil servants might be discouraged to respond to them on time due to an inconvenient, complicated task structure.

Cognitive overload: The cognitive load is the amount of mental effort and memory used at a given moment in time. Overload is when the volume of information provided exceeds an individual's capacity to process it. We have limited amounts of attention and memory, which means we cannot process all the information available. Civil servants often face many simultaneous tasks and might not process all of them with the same level of attention and timeliness.

Behavioral Tools

Salience: Our attention is limited. Therefore, behavioral economics pays special attention to when a message is delivered, the location at which it is delivered, and the content it emphasizes. Making key elements visible and prominent at the proper time and place is vital and just as necessary as the message's main content. In this case, the notification of an information request was restructured, and key elements were made more salient.

Loss aversion: Refers to the idea that a loss causes distress that is greater than the happiness caused by a gain of the same size. Civil servants in the treatment group were informed that a lack of response might trigger prosecution with both human and economic resource losses. While the notification to the control group also contained this information, the treatment group’s wording was designed to trigger loss aversion.

Simplification: Reducing the effort required to perform an action by making the message clearer, cutting the number of steps or breaking down a complex action into simple and easier steps. In this case, the notification request was restructured to increase clarity, and tasks were broken down into simple steps, accompanied by icons providing visual support.

Prescriptive norms: Refers to whether society approves or disapproves certain behavior—that is, describes it as good or bad. These norms exist regardless of whether society follows this behavior, and they are useful for reaffirming or recognizing good individual behavior while discouraging bad behavior. The notification highlighted that access to information is a human right and that it is up to everyone to defend it.

Feedback: It is an effective tool to enhance awareness of the consequences of various choices. It may fill knowledge gaps and foster the search for efficient alternatives. In this case, feedback was provided on the percentage of requests that was not processed on time, thereby highlighting the undesired outcome.

Intervention Design

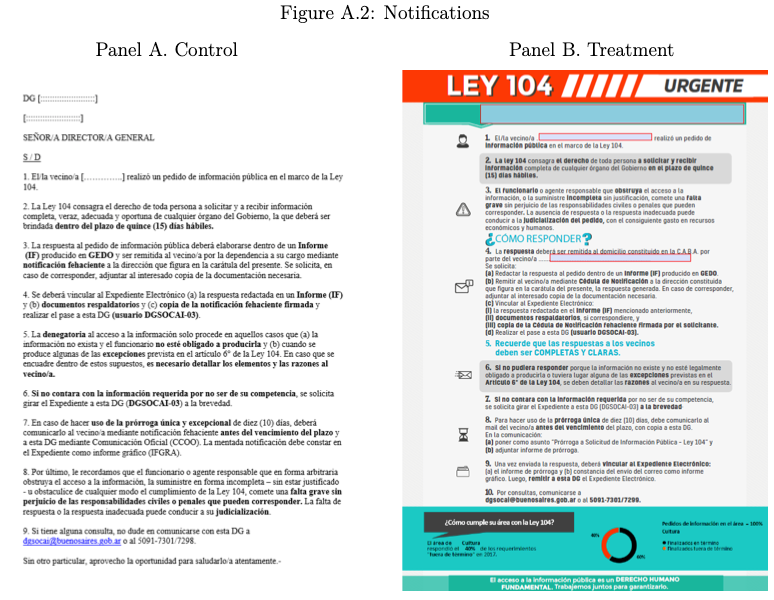

The project measured effects of two approaches: a traditional workshop and a behavioral intervention. The design of the latter was based on a diagnostic of causes why civil servants might miss deadlines to answer requests under the Freedom of Information Act. One essential conclusion was that civil servants did not understand the deadlines and procedures well, nor were they aware that timely compliance was a priority for the city government. The theory of change to achieve improvement was built on modifying and redesigning the notification that the directorate processing the requests sends out to specific agencies.

The intervention used a stratified randomization procedure to assign agencies to treatment and control groups: 121 agencies were split into the control group (62) and the treatment group (59). The unit of observation was individual citizens’ requests, with 3,785 observations before and 3,111 after the intervention began. While the control group received the “original” notification request, the treatment group received the redesigned one (see Figure 1). The behaviorally informed redesign notification relied on several insights, by 1) increasing the visual salience of the request, 2) adding an element of deterrence in form of loss aversion, 3) simplifying and 4) personalizing the information 5) providing feedback, and 6) activating social (injunctive) norms.

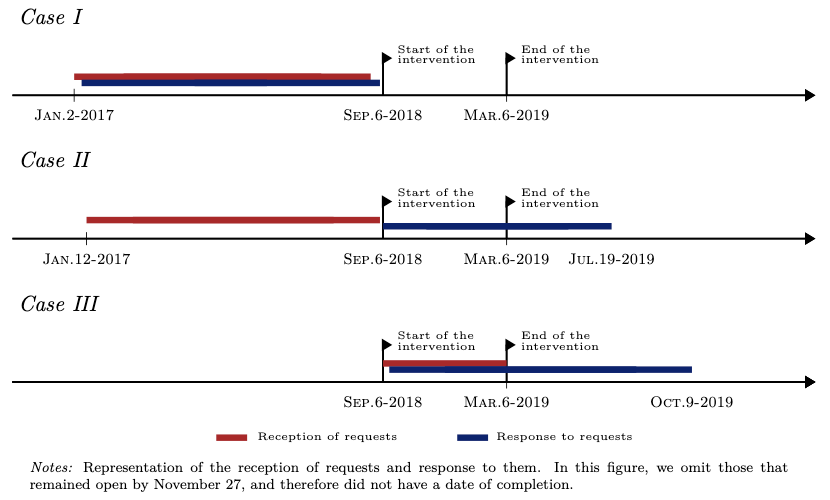

Since the intervention was implemented while requests continued to be processed and received, three different cases were classified for the following analysis. Cases that were answered before the start of the intervention (case 1); cases received before but not yet answered (case 2); and cases only received after the beginning of the intervention (case 3); see Figure 2. The overall period of observation recorded pre-intervention baseline data starting in January 2017. The intervention took place between September 6, 2018, and March 6, 2019, and the last date included for analysis is October 9, 2019.

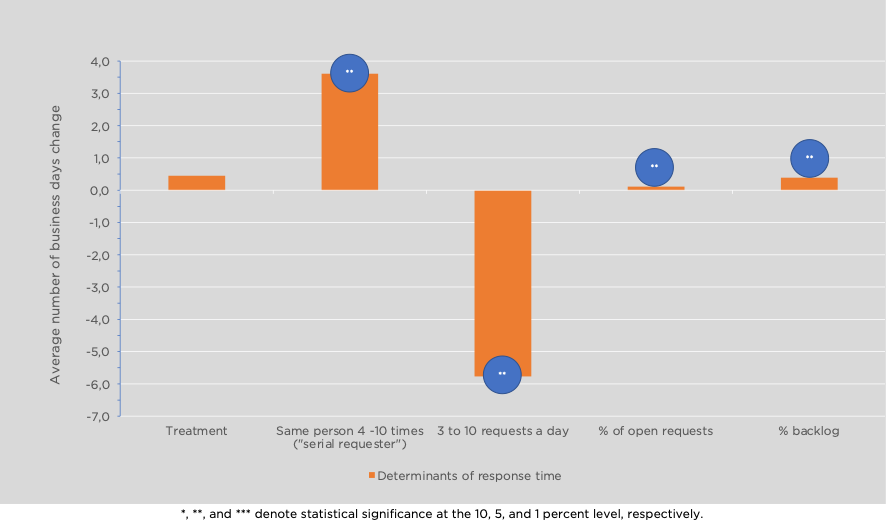

The dependent variables of the analysis included the number of business days needed by each agency to respond requests: binaries for responding within the first period of 15 days, for requests answered on the first deadline day (15th day); within the extension period (between 16 and 26 business days); on the deadline day of the extension period (25th day); and for late submission (after the second deadline). The analysis further includes three covariates to control for request workload and backlog as well as variables for serial requesters who submit with a high frequency. In the sample, serial requesters represent 41,3 % of the data.

Figure 1. “Traditional” and Re-Designed Notification Letter to Citizen Requests.

Figure 2. Different Cases and Timelines for Procedures.

Challenges

- Although disentangled in the analysis, the simultaneity of the two interventions might have led to undiscovered confoundment of the results.

- The longevity of behavioral interventions’ impact strongly depends on the context. In this design, the period of observation post-intervention was six months, potentially limiting a generalization of sustained effects over a longer term.

Results

- The behavioral intervention (redesigned letter) was successful in increasing the response to a request exactly on the second deadline day by 5.8 percentage points (pp). This represents an increase of 64% with respect to the mean in the pre-treatment stage.

- The results indicate a substitution effect: while fewer requests are answered during the extension period, there is an increase in answering them on the last two days. This is evidence that, while the treatment did not alter the whole distribution, it made deadlines more salient and civil servants adhered more to them.

- There are also positive spillover effects of the modified request notifications on responding to requests that had been received before the intervention (Figure 3).

- Attending a workshop significantly delayed responses to a request. It increased the likelihood of responding during the extension period by 5.3 pp and the average duration of processing a request by 7.8 days. The results can be interpreted as a reaffirmed commitment on the part of civil servants to work towards high-quality responses, which requires more time.

- In comparison to agencies in the treatment group without influences from workshops, the likelihood of answering a request late was 13.3 pp higher for agencies who were in the treatment group and attended a workshop.

- Agencies without workshop participation that received the modified notification letter were significantly more likely to respond during the extension period and on the second deadline day in comparison to the control group.

- Differences between treatment and control groups within the subset of agencies that completed the training workshop are insignificant.

- These results indicate that workshop participation potentially explains later responses across groups and might counter positive effects of the behavioral intervention.

Figure 3. Determinants of Response Time to Citizen Requests.

Policy Implications

- This study showed that behavioral interventions can have a meaningful impact on increasing civil servants’ task performance by making tasks easier to understand, more salient, and personalized.

- While civil servants’ compliance with this specific task is already high (78%), potentially indicating ceiling effects, it might be highly illuminating to explore their use in contexts of lower compliance.

- The analysis suggests that workshops might not be efficient in increasing public servants’ task performance. Given the absence of strong evidence in favor of workshops in the literature, this result further indicates the need to evaluate the conditions under which training could work.

- Behavioral interventions might lead to an improvement in civil servants’ tasks performance, but the effects could be overshadowed by another policy with adverse effects (workshops).

- The study showed the need to understand the systemic contexts in which interventions are conducted.