Report Cards: Parental Preferences, Information and School Choice in Haiti

Context

Haiti's education sector faces significant challenges, reflective of the country's status as the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. Unlike most Latin American and Caribbean countries, Haiti's education system is predominantly private, with approximately 75% of primary-aged students attending private schools. Public schools, which are fewer, often lack the necessary infrastructure and resources, prompting many parents to choose private schools despite financial constraints.

The rapid growth of the private sector has not been matched with adequate regulation, leading to significant variations in school quality. Parents, working with incomplete information, often make school choices that do not align with their preferences. This results in inefficiencies in the education market, as decisions are based on noisy and incomplete observations of student performance and instructional quality.

This study addresses the critical issue of information asymmetry in the Haitian education market by providing parents with accurate and accessible information about school performance. Parents can therefore make better-informed decisions, potentially leading to improved educational outcomes.

Project

We partnered with researchers from various institutions to conduct a randomized controlled trial (RCT) across 763 schools in rural Haiti to assess how providing parents with information about school performance affects school choice and market outcomes. The experiment included three nudges: i) school report cards that provided the relative ranking of schools within an area, ii) workshops to help parents understand and utilize this information, and iii) meetings with school administrators. The intervention provides insight into how information provision can enhance educational markets in developing countries.

Behavioral Barriers:

Lack of Information: People may lack relevant information because, for instance, information is difficult to obtain, scarce, or hard to understand. In the context of rural Haiti, parents have little information on the quality of schools in their area and thus are unable to make informed decisions.

Availability heuristic: Persons tend to use mental shortcuts based on immediate examples that come to mind when evaluating decisions about the future. In an imperfect information environment, parents may make school choices based on readily available information, such as personal experiences, word-of-mouth from neighbors, or visible school characteristics like infrastructure. This can result in biased decisions where parents overestimate the quality of schools they are familiar with and underestimate the quality of lesser-known schools, regardless of actual information.

Behavioral tools:

Information: Frequently, the target population does not have the information needed to make a decision, and providing the information is sufficient to nudge people into a decision and consequently undertaking a beneficial action. In this context, providing parents with information on the relative prices and performance of schools in their area through report cards and billboards results in a revision of existing beliefs. Parents can therefore make better-informed decisions that positively affect their children’s outcomes.

Framing: The way information is presented can have a big impact on people’s understanding of it, and on the actions they take. For example, highlighting the negative aspect of a decision can cause an option to be perceived as more—or less—attractive. To emphasize the differences between schools in an area, we inform parents of a school’s performance by ranking them in descending order using symbols that are easily understood by parents in this context.

Design & Challenges

The experiment was structured as a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and involved a sample of 763 schools divided into 84 clusters or educational markets across rural Haiti. Each cluster contained at least one primary school, with schools within each cluster located within a one-kilometer radius of each other. The clusters were randomly assigned into a treatment group and a control group, each containing 42 clusters.

The treatment consisted of three nudges:

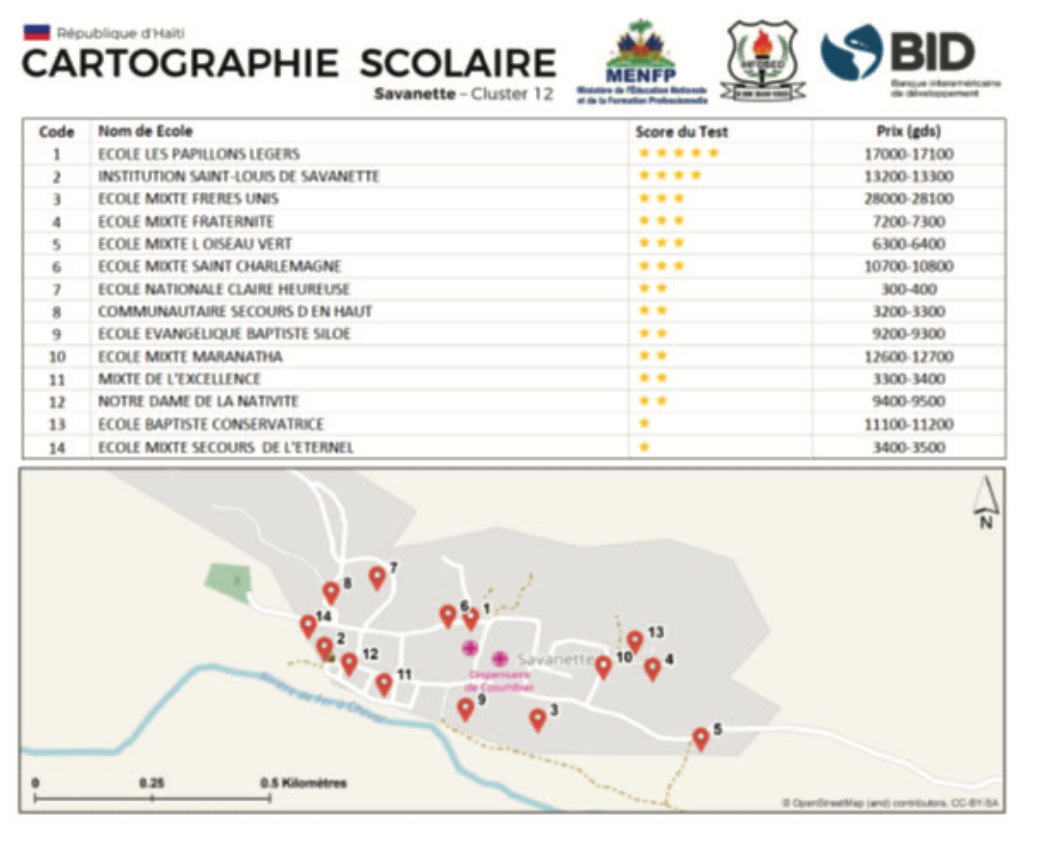

i) The distribution of easily understood school report cards that provided the relative ranking of schools as well as their location within the given cluster. Schools were ranked based on the average student test performance in the baseline assessment. Schools received three stars for performance at the mean and each star above/below represented one standard deviation. The report also presents the price of attendance for each school within the cluster.

ii) Workshops for parents to help them understand and utilize this information effectively. This activity included creating a space for parents to discuss freely the schools their children attend or would prospectively attend.

iii) Meetings with school administrators regarding the management, operations, and pedagogy of the school.

In addition, parents were also encouraged to use the information on student performance and teacher absenteeism in meetings with school administrators. The new information and collective action were seen as a way to improve the bargaining position of parents as they sought to improve the quality of instruction students received.

Before the intervention, baseline data were gathered through a standardized national examination designed for students, a survey of parents, and a survey of school administrators. The examination provided baseline data on student performance in each school, the survey of parents provided information on how parents gathered information regarding school quality, and the survey of administrators provided information on school management and fees.

Approximately one year after the implementation of the study, an endline survey was conducted. The survey captured the educational outcomes of a subsample of students using the national assessment from baseline and gathered parents and administrators’ current perceptions on school quality.

Challenges

During the study, some schools closed or did not participate in the endline assessment. Specifically, of the original 763 schools sampled, data could not be recovered from 168 schools by the endline period. Notably, attrition did not affect the balance between the treated and control groups.

Hypothesis: The intervention is expected to better equip parents with the ability to assess whether the prices they pay for private education coincide with the quality of instruction their children receive. With this information, parents can take action and call for improvements in school quality and/or potentially enroll their children in other schools. Schools in the treated group will respond to this pressure by adjusting fees, investing in infrastructure and instructional quality, or closing altogether. The increased information in the market allows parents to act in line with their preferences, and prices may thus begin to possess and retain meaning in the market.

Results

- There is no significant change in tuition and other expenses charged to parents after they gather more information on school quality and increase their bargaining power.

- The intervention had a significant impact on private school average test scores, which improved after the intervention. Average test scores for students in private schools in the treated group improved by 0.302 standard deviation. There was no significant impact on public school scores.

- The intervention’s effect on test scores was mainly concentrated in private schools located in the middle and lower ends of the quality distribution at baseline. Improvements in test scores occurred only in Creole and French assessments, with no significant improvements in Mathematics scores.

- The treatment resulted in a slightly positive effect on the market share of high-quality public schools and a slightly negative effect on that of high-quality private schools. The results suggest that families could have changed their children’s schools or migrated to different clusters.

The results overall suggest a mixed impact of the intervention on fees, test scores, and market shares. Test scores improved for some private schools, and market shares increased for some public schools. The intervention likely encouraged more dialogue between school directors and parents and prompted parents to move between clusters seeking better schools or lower fees. Given the constraints in these rural markets, it is probable that parents pressured existing schools for improvements or quickly sought alternatives.

Policy Implications

Reducing information gaps can generate greater equity and efficiency in education systems, particularly in low-income settings. Understanding how information impacts school choice can help both policymakers and educators design interventions that enhance the overall quality of education.