How to Best Remind Taxpayers of Their Obligations

Context

There is growing interest in explaining what motivates individuals to pay their taxes in full and on time, and the best way to deal with tax delinquency. While many studies have evaluated the comparative effect of sending deterrence and moral suasion messages to taxpayers, an experiment conducted with the National Tax Agency of Colombia(Dirección de Impuestos y Aduanas Nacionales, DIAN), analyzes how different methods of delivering the same message affect tax compliance. The agency contacted taxpayers with outstanding tax liabilities through in-person inspector visits as well as cheaper methods such as email and letter. Tax inspectors’ visits are expensive, signaling the severity of the consequences of noncompliance.

The Project

Once every few months, DIAN contacts taxpayers with outstanding liabilities (declared but unpaid taxes) by mail and email, sometimes also making sporadic in-person visits. On one occasion, the agency agreed to randomize the delivery mechanism of such messages to test their comparative efficiency.

The messages were sent out in both a physical letter and email, which were identical. They included moral suasion and information on the pending payment, as well as an explanation of the consequences of sustained tax delinquency. More than 20,000 taxpayers participated in the experiment.

Behavioral Analysis

Behavioral Barriers

Prescriptive norms: These refer to what society approves or disapproves of—that is, what is considered to be right or wrong—regardless of how individuals actually behave. Such norms are useful for reaffirming or encouraging what are considered positive individual behaviors while discouraging negative ones. In the context of our study, the acceptable behavior is to pay taxes when they are due to the government.

Present bias: It is the tendency to choose a smaller gain in the present over a large gain in the future. It is related to the preference for immediate gratification. It is also known as hyperbolic discounting. People with such a bias might value present gratification more than greater benefits in the future—for example, they might avoid paying taxes even when there is a possibility of winning a lottery

Optimism bias: It leads us to underestimate the probability that negative events will happen to us and to overestimate the probability of positive events. For example, taxpayers with optimism bias might underestimate the possibility that the government will identify their tax delinquency.

Availability heuristics: Individuals tend to estimate the probability of a future event based on how readily representative examples of such an event come to mind (i.e., punitive actions that have been taken against delinquent taxpayers in the past).

Salience: Individuals tend to focus on items or information that are more prominent and ignore those that are less so. Thus, it is important to make key aspects of messages visible and salient and display them in an appropriate place and time.

Other Barriers

Mistrust: Mistrust occurs when one party is unwilling to rely on the actions of another party in a future situation. In response to corruption scandals, citizens may mistrust their representatives in the government. Taxpayers who do not trust a government administration may use this as a justification for tax evasion.

Behavioral Tools

Signaling: The act of conveying credible information to others about one’s expected actions or behavior.

Moral suasion: A person or group may be persuaded to act in a certain way through theoretical appeals, or implicit and explicit threats.

Intervention Design

In the context of this project, the agency randomized a subset of taxpayers with overdue tax payments into four main groups. One group was assigned to be contacted via e-mail, the second one via physical letter, and the third group was assigned a visit from an inspector. The fourth group was left as a control group. The population of this experiment included all taxpayers with unpaid liabilities from their income, wealth, or sales taxes for the years 2011–13.

The population that remained eligible was 20,818 taxpayers. Among them, 5,000 taxpayers were assigned to standard mail, 5,000 taxpayers to email, and 4,042 to a personal visit; the remaining 6,776 taxpayers were assigned to the control group. The randomization was performed in six blocks according to the size of debt and whether the debt was recent or not.

The message included in both the physical letter and the email was exactly the same. The message stated the account balance on July 31, 2013, the type of tax, and the year or month it had not been paid. It also included information on methods of payment and the cost that the taxpayer was incurring by not paying (interest and penalties, potential legal action, and possible effect on credit history). Finally, it provided a moral suasion message (“Colombia, a commitment we can’t evade”). The message concluded with the contact information of a tax agency authority. This way, even though the content of the messages was not the subject of the evaluation, careful steps were taken to include all the components that have been identified in the literature as critical to increasing compliance.

During the in-person visits, inspectors followed a protocol aligned with the written communications that had been sent out: the taxpayer was informed about his or her standing tax delinquencies and was urged to pay. Inspectors mentioned the penalties the taxpayer was incurring and the possibility of further legal actions in case of noncompliance. The visit was closed by the verbal delivery of a moral suasion message.

Challenges

The relative difference in marginal cost between an inspector’s visit and sending a letter is high (about 16 times). However, in the case of Colombia, the absolute cost of an inspector’s visit is relatively low. This might not be the case in some other contexts.

Results

Results indicate large and highly significant effects, as well as sizable differences across delivery methods.

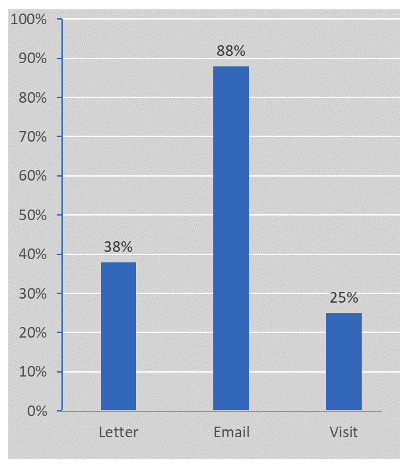

- The agency faced difficulties delivering its messages to subjects across the different treatment groups, due to the limited time of the personnel involved and out-of-date contact information. This translates into fewer subjects reached per treatment, as shown in figure 1.

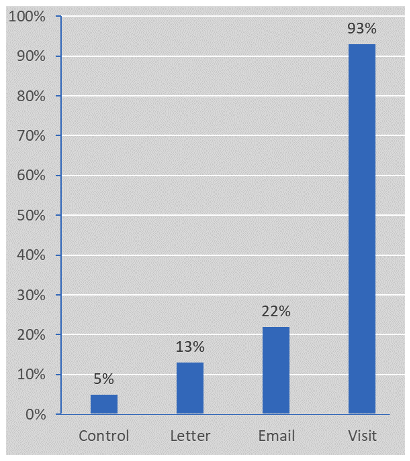

- Further analysis of each communication channel reveals that the payment of outstanding debt was about 8 percentage points higher for those who received a letter than for the control group (figure 2). For recipients of emails, payments were 17 percentage points higher and for those who received an in-person visit, 88 percentage points. Thus, almost every person who received a visit from a tax inspector made some kind of payment.

- These results suggest that a visit from a tax inspector is more effective than a physical letter or an email, which are conditional on delivery. Email, however, tends to reach its target recipients more often than mail.

Figure 1. Share of Taxpayers Reached by Assigned Treatment

Figure 2. Share of Taxpayers Who Made Payments

Policy Implications

- Informational taxpayer campaigns on pending liabilities are good mechanisms for increasing compliance.

- Sending tax inspectors for in-person visits is significantly more expensive than sending letters and emails, but it is a more effective way of signaling to taxpayers the severity and the consequences of noncompliance. This is likely the reason why those who received visits also cancelled other pending obligations.

- It is important to maintain a clean, up-to-date database of taxpayers that includes physical and electronic addresses to run interventions like this one more efficiently. Having a valid address could have doubled tax collection in this intervention.