Nudging parents to vaccinate their daughters with social norms text messages

Context

According to the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, cervical cancer is the leading cause of death from cancer among women aged 30 to 59 years in Colombia. Unlike many other cancers, this type is mainly caused by a virus: the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), which can be transmitted through oral, vaginal, or anal sexual contact. The prevalence of HPV in Latin America and the Caribbean is 16%, the second highest in the world after countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (24%). Fortunately, the risk of HPV infection and the risk of developing this type of cancer can be prevented through a vaccine administered free of charge in Colombia to girls and adolescents between the ages of 9 and 17. However, HPV vaccination coverage in Bogota is lower than expected, and only 6% of 9-year-old girls are fully inoculated with two doses of the HPV vaccine.

The Project

To increase the HPV vaccination rate in Bogotá, the Behavioral Economics Group sent text messages with behavioral economics principles to parents of girls between 9 and 17 years, in coordination with the Secretariat of Health of Bogotá, the Ministry of Health of Colombia, the American Cancer Society (ACS), the Liga Colombiana Contra el Cáncer and The Behavioral Government Lab at Universidad del Rosario. The complete intervention targeted a total of 174,181 parents. From that sample, 75% were nudged to vaccinate their daughters for the first time, while the rest were parents of girls and adolescents pending one vaccine who were reminded to complete the entire vaccination scheme of two doses. This project summary presents two out of the six experiments run during the whole project. Both experiments were designed with the behavioral tools of social norms. The intervention took place between October 2021 and December 2021.

Behavioral Barriers:

Salience: Our attention is limited. Therefore, behavioral economics interventions carefully consider the moment when a message is delivered, the location in which it is delivered, and the content it emphasizes. In this context, parents are unsure when they should vaccinate their daughters against HPV and wait for the doctors to recommend vaccination. However, all the doctors interviewed reported limited time during appointments, and more urgent issues took priority over HPV. The absence of discussions and reminders leads parents to assume passive attitudes toward HPV vaccination. In general, there is a lack of moments of reflection, choice, and opportunity to take action on HPV vaccination for girls aged 9-17 in Bogotá.

Mental accounting: Mental accounting is our tendency to mentally sort our money into separate “accounts,” leading us to see money as less fungible than it is and affecting our spending behavior. The concept is usually applied to personal finances, but in this context we apply it to the use of time and activity. In the case of children’s vaccines, although the vaccine is part of the full vaccination scheme, parents do not put the same amount of effort into vaccinating their daughters against HPV as for other vaccines deemed “more essential.” Evidence from our interviews indicates that parents mistakenly view vaccination as no longer a significant priority in children's health considerations after five years of age.

Mistrust: Mistrust occurs when one party is unwilling to rely on the actions of another party in a future situation. Government support for the HPV vaccine has waxed and waned in the past, adding complexity to parents’ decision to vaccinate their daughters. Health professionals believe that a more explicit endorsement from the government would increase trust and make parents more likely to accept the vaccine recommendation. Parents interviewed in the diagnostic phase of our study expressed their desire for the government to take a more explicit stance on their support of HPV vaccinations.

Present bias: Present bias, associated with a preference for instant gratification, is the tendency to opt for a lesser benefit in the short term over a greater benefit in the longer term. Because immunity is not tangible, it is difficult to appreciate the benefits of vaccination in the short term. In addition, there is no immediate consequence for failing to receive the HPV vaccine; this stands in contrast to, for example, the requirement of certain immunizations for children 0-5 years in order to be admitted to school. It thus becomes easy to put off the decision about HPV vaccination to the future.

Behavioral Tools:

Social norms: The unwritten rules governing behavior within a society are called social norms. In this project, we used a variety of social norms tools: i) descriptive social norms, ii) prescriptive social norms, iii) dynamic social norms, and iv) trending social norms.

Descriptive social norms: These norms describe how a social group behaves, without regard for whether the behavior is good or bad. These norms are usually communicated using factual data, and learning about them can help change behavior. In Bogotá, at the time of our experiment, 2 out of 10 parents had vaccinated their daughters against HPV for the first time, and less than 1 out of 10 parents had vaccinated their daughter against HPV twice (we faced a minority descriptive norm). However, we had to stay true to the data and send messages communicating the minority descriptive norm.

Prescriptive social norms: Refer to whether society approves or disapproves of a particular behavior—that is, describes it as good or bad, regardless of whether society follows this behavior. Such norms are useful for reinforcing or recognizing good individual behavior while discouraging bad behavior. For this experiment, we added a sad face emoticon after the descriptive norm to indicate that lack of vaccination is unacceptable behavior.

Dynamic social norms: Are defined as social norms about how other people's behavior and attitudes change over time; such norms highlight and encourage novel ways of thinking and behaving. At the time that we ran our experiment, a minority of people had vaccinated their daughters against HPV; thus, in our context, the descriptive social norm in Bogotá communicated that others were not engaging in the desired behavior. This might encourage some parents to likewise refrain from vaccinating their daughters. To promote vaccination, we crafted messages suggesting that current vaccination levels are just the beginning of a trend and not merely a minority social norm.

Trending social norms: Are defined as social norms in which the number of people engaging in a behavior is increasing or decreasing. Presenting social norms as trending is a strategy for leveraging normative information to increase conformity to behaviors not yet performed by a majority (or to decrease an undesirable behavior). The mechanism emerges because people predict the increase in prevalence of the desired behavior will continue and will become a norm in the future. Since we faced a minority descriptive norm in Bogota, we used historical information to compute the percentage increase of vaccinations since a strategically selected year (vaccinations in Bogotá in 2016).

Qualitative social norms: Refers to the representation of the descriptive social norm in a qualitative rather than the more commonly used quantitative way. As with the quantitative approach, qualitative social norms can also be presented as a static picture or as time-evolving. For example, a qualitative descriptive social norm would be, “The majority of parents have vaccinated their kids against [disease],” while a qualitative dynamic norm would be, “More and more people are vaccinating their kids against [disease].” We used qualitative social norms to craft a dynamic message for the group of parents who had not vaccinated their daughters for a second time against HPV.

Intervention Design

The Behavioral Economics Group, in coordination with the Secretariat of Health of Bogotá, the Ministry of Health of Colombia, La Liga Colombiana Contra el Cáncer, the American Cancer Society, and the Behavioral Government Lab at Universidad del Rosario, implemented several SMS experiments designed to increase HPV vaccination rates in Colombia. All the experiments were implemented through a text message campaign (SMS), differing in the behavioral tool used to prepare the message. Our team decided on this channel because the Secretariat of Health in Bogotá had already launched several SMS campaigns in the past. In this summary, we will explain two experiments designed with social norms.

The two social norms experiments differ from each other in their target population and slightly in their content. The first experiment targeted the parents of girls that had never been vaccinated against HPV in the past. The second experiment targeted girls’ parents who had received the first dose but had not yet completed the whole scheme of two doses. The number of parents who participated in the first-dose experiment was 34,506, and in the second-dose experiment was 15,376. Table 1 shows the messages we designed in experiment one applying different versions of social norms as their behavioral design tool, and Table 2 shows the messages crafted for the second experiment.

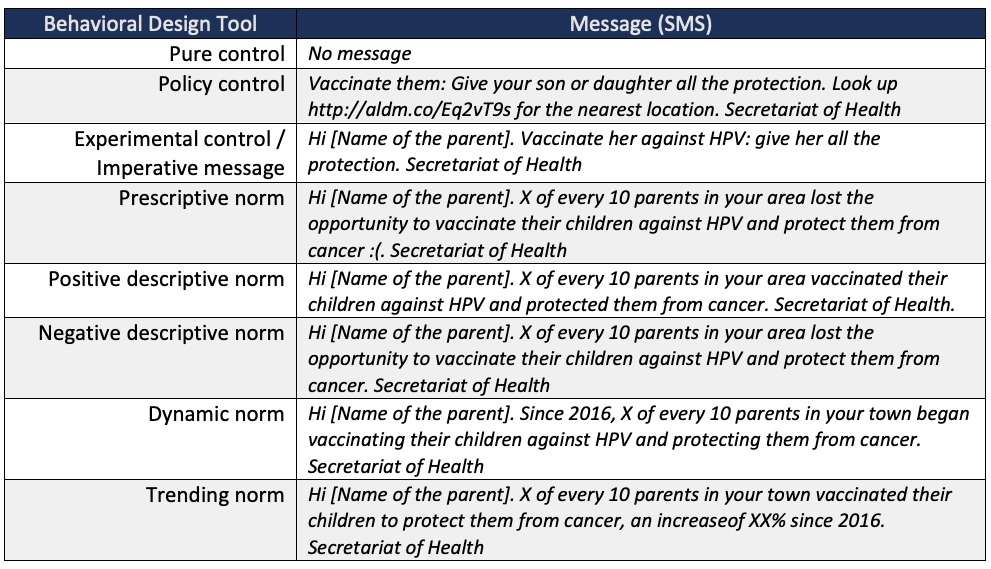

Table 1. Message content by behavioral design tool for experiment one (first dose)

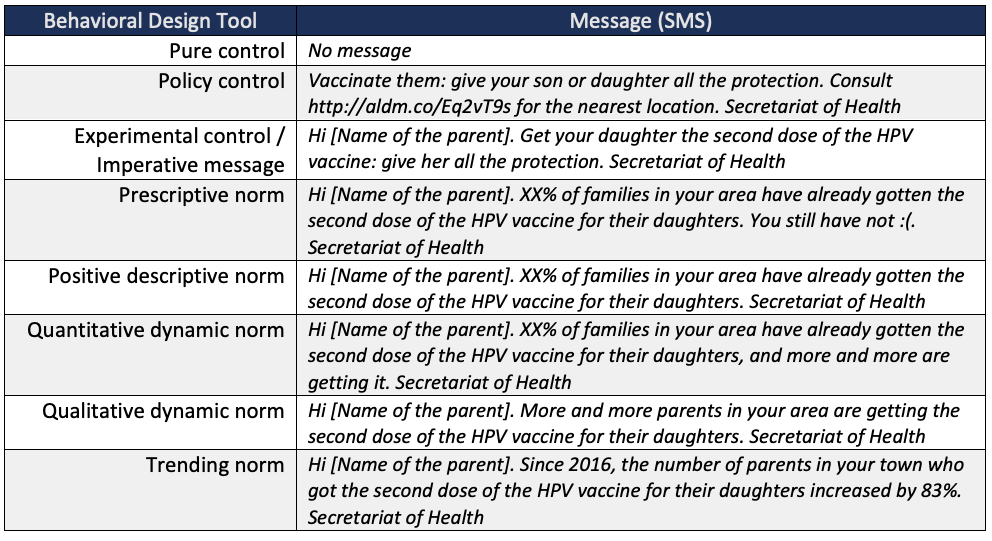

Table 2. Message content by behavioral design tool for experiment two (second dose)

As Table 1 and Table 2 show, all the experiments included five treatments designed with social norms elements and three control groups. The pure control group did not receive any message. The policy control group received the "business as usual" message that the Secretariat of Health of Bogotá was using in communications with the target population. The experimental control group included fixed elements that were incorporated into every treatment. The fixed elements for this social norm experiment were a customized greeting with the parent’s name and the Secretariat of Health’s signature. Each treatment tested a specific behavioral tool combined with the fixed elements in the experimental control.

The experiments consisted of sending a weekly text message to the target population’s parents over an eight-week period. The content of the message remained constant. The vaccination records of the Secretariat of Health are updated daily, and our team received them weekly. This allowed us to remove those parents who had already taken action before we sent the following message.

The social norms experiments exploited alternative ways to communicate the social norms regarding HPV vaccination, which is not generally discussed in parent-to-parent conversations. We believe that by conveying that vaccination against HPV is a norm—the desired behavior—parents will be more likely to act on it and protect their daughters against HPV and, consequently, cervical cancer. Additionally, choosing the right reference point is important when designing social norms messages. In most of the messages in these experiments we were able to provide information about vaccination rates at the area level (localidad). Messages to parents were customized so the information received was as relevant for them as possible. This elevates the power of the social norm by increasing the potential for parents to identify with their peers.

Challenges

This project had several challenges:

- Despite our team’s solid credentials, it took considerable effort to create rapport with government employees at the Secretariat of Health. Specifically, the Secretariat of Health’s ethics committee asked us to make significant revisions to our ethics materials, even though the project had already gone through the ethics committee at Universidad del Rosario.

- Related to that, it was not easy or fast to get the correct data set from Secretariat of Health's records because it took time to synchronize our team’s needs with the correct data extraction from administrative records.

- Another obstacle was that the proposed government’s partner agency could not send the text messages, so we had to find an alternative platform to send SMS. We used a platform that we had previously worked with (Altiria), and our team programmed and sent the SMS. The upside is that we gained control over the experiment. However, we lost the opportunity to train government officials on these interventions.

- HPV vaccines ran out after week 4 of our intervention in some vaccination centers. We had to stop sending SMS and helped in the coordination between the Ministry of Health and the Secretariat of Health. They quickly responded, and we were able to resume the experiment after pausing it for ten days.

Results

Results indicate that the SMS intervention increased first-time and second-time HPV vaccination rates in Bogotá.

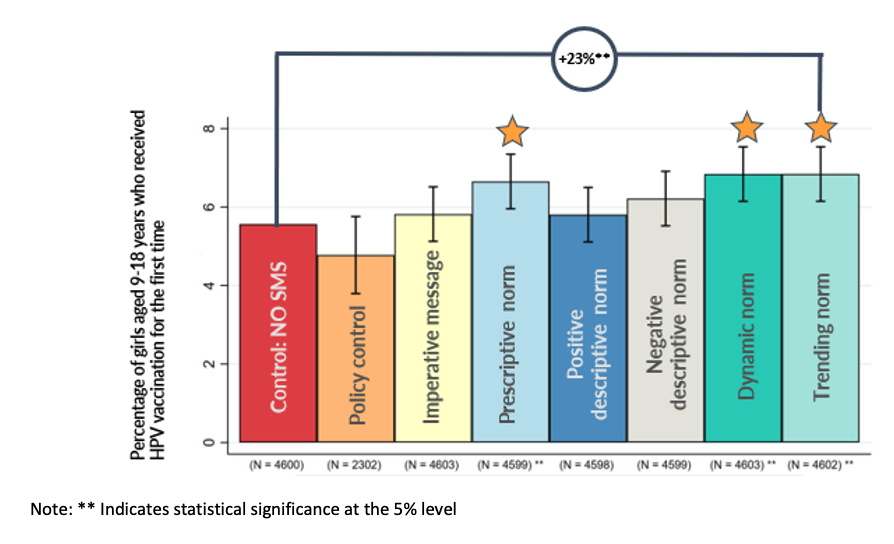

- The most impactful treatments for increasing first-time vaccinations, with equal effectiveness, were the dynamic norm treatment and the trending norm treatment (see Figure 1). These two treatments had an average vaccination rate of 6.8%, which represents a 23% increase compared to the control group.

- Closely behind was the impact of the prescriptive social norm treatment with a vaccination rate of 6.7%, which represents a 20% increase of first-time vaccination rates compared to the control group.

- Although the policy control was not statistically significantly different from the pure control, the total number of vaccinated girls in this group was lower than the pure control. This indicates that messages that do not incorporate behaviorally informed insights can potentially backfire, thus disincentivizing vaccination.

Figure 1. The dynamic, trending and prescriptive norms were the most effective at getting parents to vaccinate their daughters for the first time

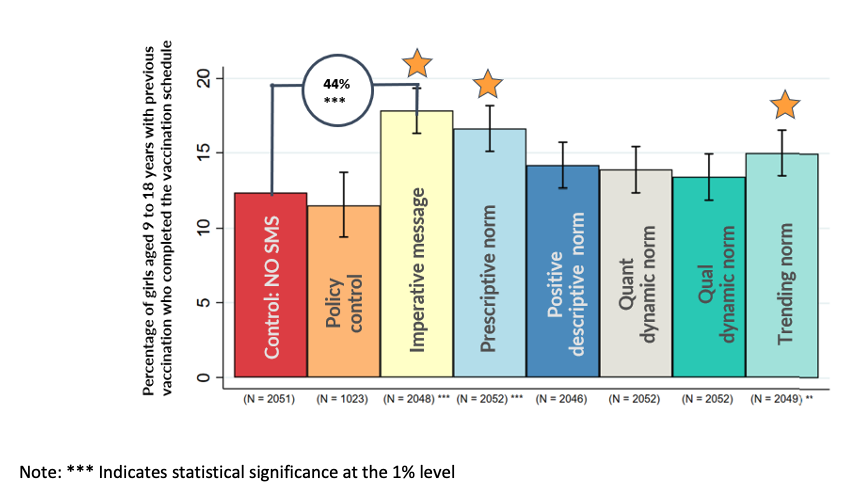

- The most impactful treatment for increasing second-time vaccination is the imperative message (see Figure 2). This treatment had a vaccination rate of 17.8%, representing a 44% increase compared to the control group.

- Closely behind was the impact of the prescriptive social norm treatment. This treatment had a vaccination rate of 16.6%, representing a 34% increase in second-time vaccination rates compared to the control group.

- Again, the policy control had even poorer results than the control (no SMS), suggesting that sending messages that do not incorporate behaviorally informed insights may be worse than not sending messages at all.

Figure 2. The imperative message telling parents to complete their daughter’s vaccination scheme was the most effective. Trending and prescriptive norms were also impactful.

Policy implications

- Cervical cancer can be prevented with a vaccine (the HPV vaccine). Parents and their children could benefit greatly from tailored communications from trusted sources, like the Secretariat of Health. This is a low-cost intervention, and its impact can be translated into many lives saved.

- The content of the message matters. As seen in the results section above, a behaviorally informed message can be compelling; however, impersonal, seemingly random messages can be detrimental to parents’ decisions. Those messages can leave parents confused and not knowing what is being asked of them. They can potentially have a worse result than not sending messages at all.

- When implementing interventions like this one, teams and governments should work closely together to secure sufficient vaccines for the anticipated increases in demand. Otherwise, the impact evaluation could be jeopardized and both teams and governments can suffer reputational costs.

If there is a minority rule in place, i.e., the desired behavior is performed only by a minority of the target population, trending norms can be an effective way to counteract a potential detrimental effect and reinforce the desired behavior.